Once again I find myself cited, this time in this paper by Yuan TU , M.H. El Naggar , Kuihua Wang , Wenbing WU , and Juntao WU. The citation comes from my paper “A New Type of Wave Equation Program,” documenting the development of the ZWAVE computer program. The abstract of this paper is as follows:

A fictitious soil pile (FSP) model is developed to simulate the behavior of pipe piles with soil plugs undergoing high-strain dynamic impact loading. The developed model simulates the base soil with a fictitious hollow pile fully filled with a soil plug extending at a cone angle from the pile toe to the bedrock. The friction on the outside and inside of the pile walls is distinguished using different shaft models, and the propagation of stress waves in the base soil and soil plug is considered. The motions of the pile−soil system are solved by discretizing them into spring-mass model based on the finite difference method. Comparisons of the predictions of the proposed model and conventional numerical models, as well as measurements for pipe piles in field tests subjected to impact loading, validate the accuracy of the proposed model. A parametric analysis is conducted to illustrate the influence of the model parameters on the pile dynamic response. Finally, the effective length of the FSP is proposed to approximate the affected soil zone below the pipe pile toe, and some guidance is provided for the selection of the model parameters.

The topic is an interesting one which I have touched on over the years. It seems to me that their characterisation of the model as “novel” may be a bit of a stretch but their implementation of it is very interesting.

What is a Fictitious Pile Model?

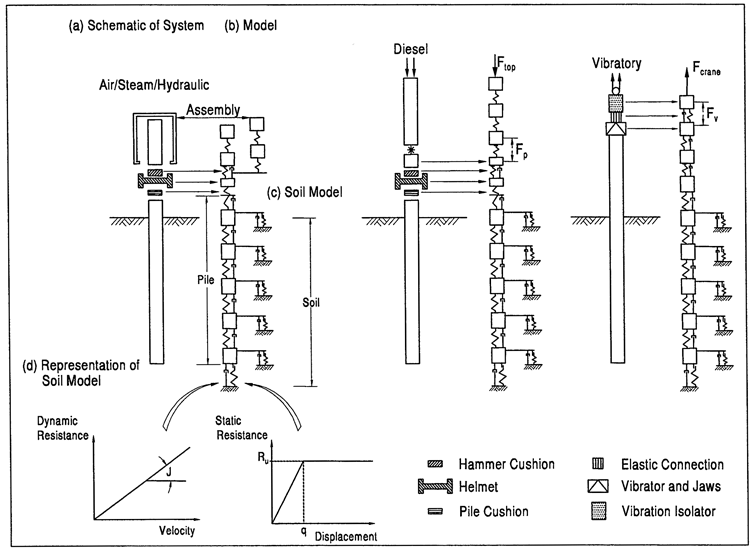

Most of us in the driven pile industry are familiar with the one-dimensional wave equation, which divides up the pile into discrete segments/elements and by doing so models the distributed mass and elasticity (or plasticity) or the system, such as is shown in Figure 1, from the Design and Construction of Driven Pile Foundations, 2016 Edition:

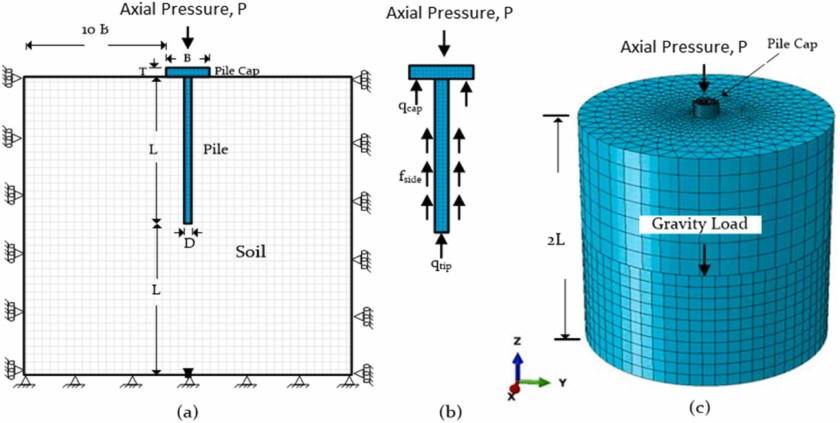

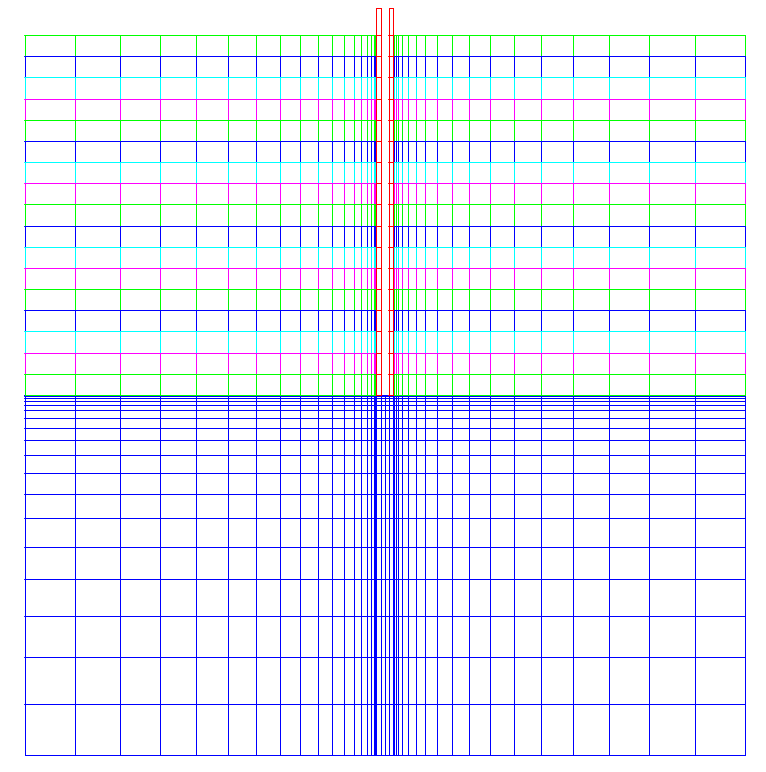

An advance of this is the use of two- or three-dimensional elements in a finite element scheme, such as was featured in the earlier post Comments on “3D FE analysis of bored pile- pile cap interaction in sandy soils under axial compression- parametric study” and was analysed extensively in my dissertation Improved Methods for Forward and Inverse Solution of the Wave Equation for Piles. A cross section of that model is shown in Figure 2, from Inverse Analysis of Driven Pile Capacity in Sands:

Note that the pile, which is in red, is basically a one-dimensional string of elements with distributed mass and elasticity. It’s worth noting, however, that using two- (or three- for that matter) dimensional elements enables the element to have a non-uniform stress distribution which would reflect the effect of the soil resistance, but let us set this last point aside.

Such a model as shown above models both the shaft friction along the side of the pile and the toe resistance under the end of the pile. It has been customary over the years, however, for researchers and practitioners alike to model this resistance in a rheological way. This has been easier with the shaft than with the toe, because of the complexities of the dynamic elasto-plastic response of the soil at the toe and the difficulties of establishing failure surfaces in the soil has led to many solutions of the problem.

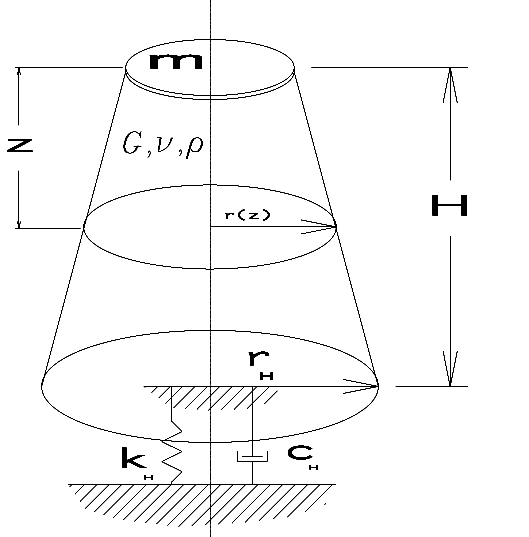

One of those is to construct a fictitious pile under the toe which, instead of the straight sides we usually (but not always) see with piles, has a conical shape, so as the distance from the toe increases the size of the fictitious pile likewise increases.

ton (1997))

The first proposal of this came from Holeyman (1988) and was discussed in Closed Form Solution of the Wave Equation for Piles and more recently in the paper STADYN Wave Equation Program 10: Effective Hyperbolic Strain-Softened Shear Modulus for Driven Piles in Clay. A diagram of this is shown in Figure 3. Although the model is generally done (as is the case in the models in Figure 1) with discrete elements, it can be modeled continuously. The paper under consideration did so using finite elements. A problem that occupied this researchers and those of the paper under consideration is the value of H, which does not have an “obvious” solution from the physics of the problem.

In the work under review, in addition to using finite elements the authors made two important improvements to the model shown in Figure 3:

- They added a “shaft” resistance along the side of the fictitious piles.

- They put a hole in the centre of the fictitious pile to assist in simulating the soil plug, which was one of the main goals of the study. Soil plugging is a difficult phenomenon in open-ended piles, and although we’ve made some progress in modelling it we still have a long way to go.

Some Comments on the Study Itself

The authors used ABAQUS to model both piles. This is a code which has been applied to geotechnical problems for at least thirty years, so it has a long track record. Having started from “scratch” with Improved Methods for Forward and Inverse Solution of the Wave Equation for Piles, I can attest that using a software package saves a great deal of time and effort, in addition to making graphical presentation of the results a good deal simpler. Having said that, if anyone has an ambition to use FEA to replace, say, GRLWEAP or CAPWAP, they’ll have to either a) pay licensing fees to a cut down “engine” from an established package like ABAQUS or b) use an open source alternative.

At the start of the study they make the following statement:

Open-ended pipe piles are increasingly used worldwide as foundations for both land and offshore structures [1,2]; therefore, the characterization of pipe pile capacity and behavior under static and dynamic loading conditions has gained much attention in recent years [3–5].

Open ended pipe piles have been used for much longer that this paragraph would imply, as this whole series will show. Getting them in the ground was much of the impetus for the TTI wave equation program, and the lateral loads they withstood were much of the push behind the development of p-y methods. And that was in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

The soil model they use is a cross between a elastic-purely plastic model and a hyperbolic soil model. Reconciling the two has been a preoccupation of this site since Relating Hyperbolic and Elastic-Plastic Soil Stress-Strain Models: A More Complete Treatment. Although the model they use certainly takes into consideration hyperbolic strain softening, I’m not convinced that their assumption that the rebound runs along the small-strain modulus of elasticity is valid. On the other hand I’m not sure what the best way out of this dilemma is; hyperbolic soil modelling hasn’t been as thorough in analysing the stress-strain characteristics of soil during rebound as it has been in doing so during loading.

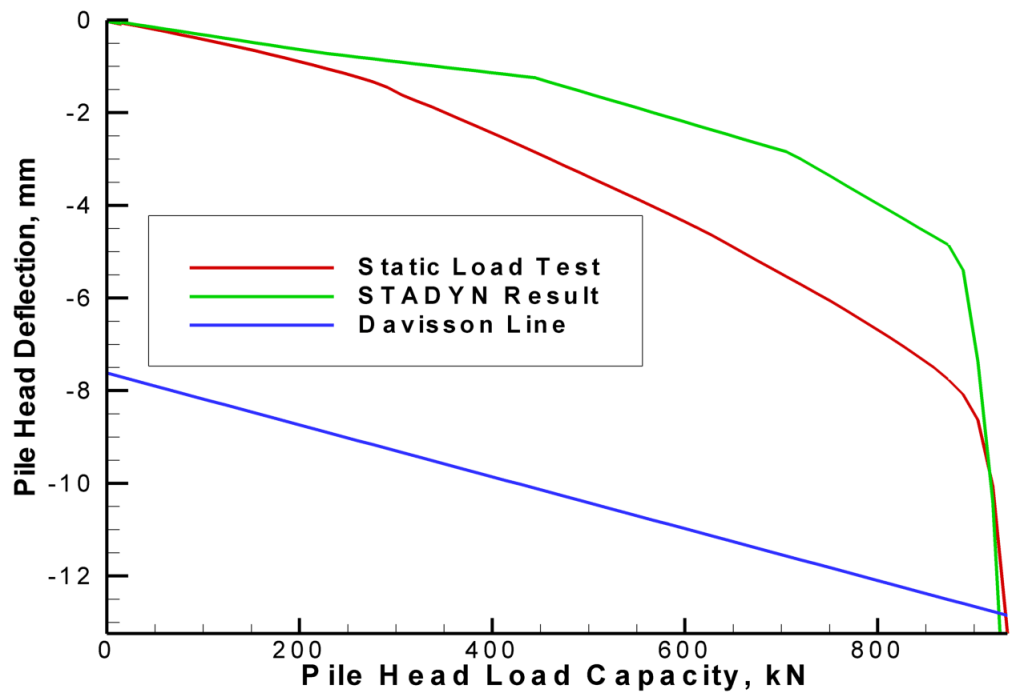

One thing I noticed is the variance between the static load test results and that shown in the model. That’s not unexpected; I’ve encountered this difficulty, as you can see from this figure in STADYN Wave Equation Program 10: Effective Hyperbolic Strain-Softened Shear Modulus for Driven Piles in Clay:

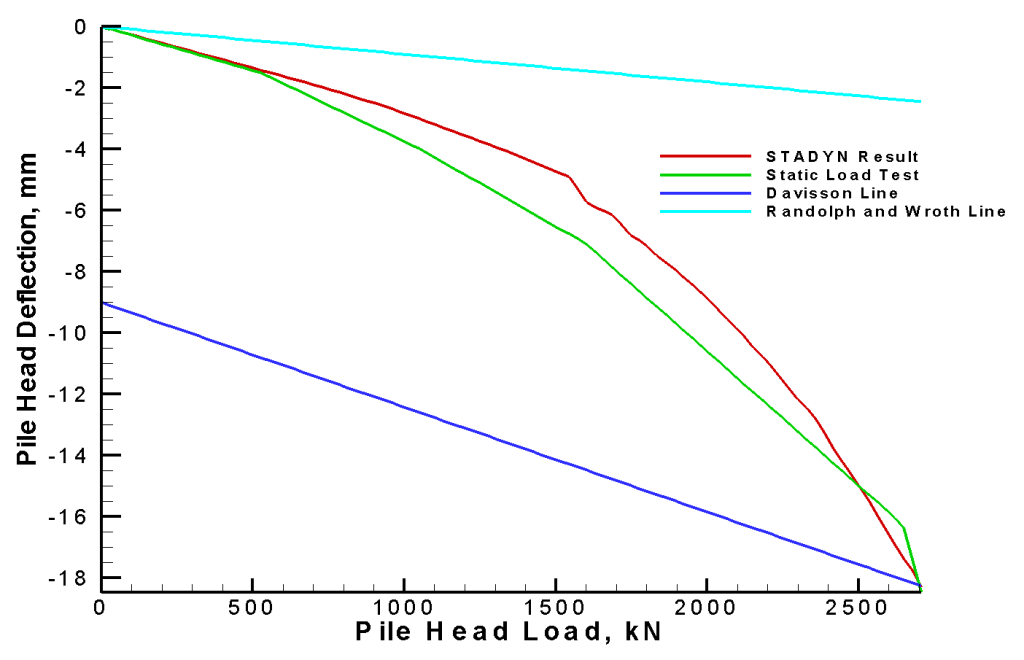

On the other hand, it’s possible to get a closer result, as is seen in Application of the STADYN Program to Analyze Piles Driven Into Sand:

The basic problem is twofold:

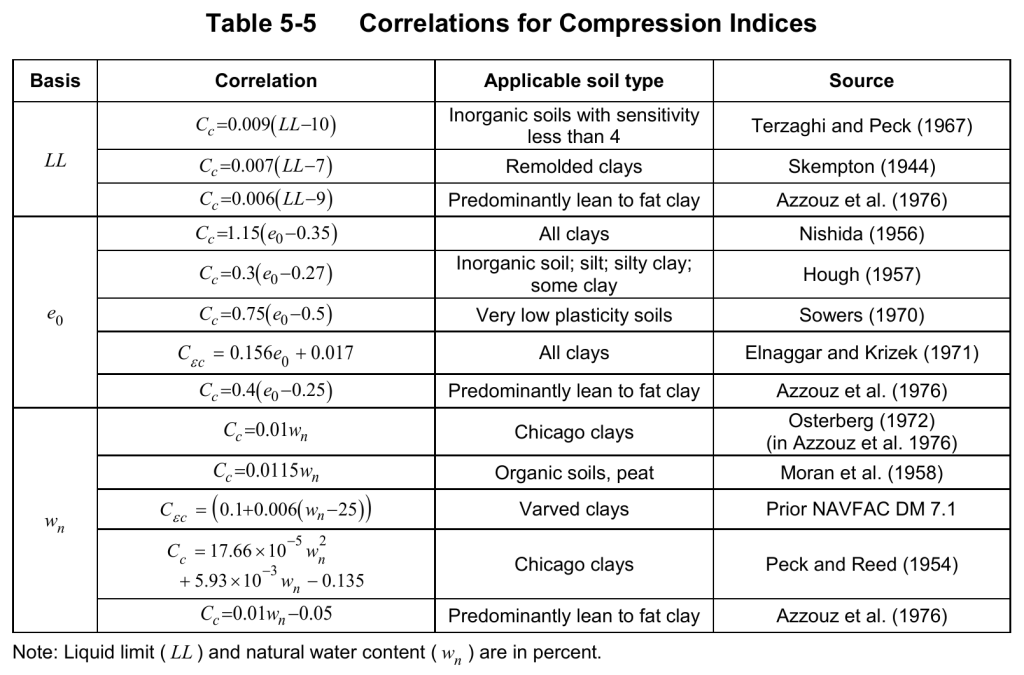

- Although the relationship between the shear modulus of soils and the void ratio or porosity is well established, the coefficient used to determine the former from the latter is subject to uncertainty.

- The static and dynamic shear moduli of soils is different, which is an issue in pile dynamics that has not been adequately explored.

Conclusion

The paper is an excellent step forward, and the model presented has a great deal of potential in pile dynamics. It may be easier to use such a model than a full axisymmetric or 3D model to obtain the inverse solution to the problem, but many of the issues discussed here–such as the angle and depth of the fictitious pile cone and the shear moduli of the soils in question–need better resolution.

As far as the plugging issue is concerned, any advance in this is welcome, although I am inclined to think that a model which simulates the full, blow-by-blow installation of the pile with the formation of the plug, will ultimately be the best solution of the problem.