In our posts Analytical Boussinesq Solutions for Strip, Square and Rectangular Loads and Going Around in Circles for Rigid and Flexible Foundations we discussed foundations on an elastic, homogeneous half-space, mostly purely flexible. In the latter post we ventured into rigid foundations but stuck with the semi-infinite spaces. In this post we’re going to explore cases where either one of the other or both of these aren’t true.

Some Review: Purely Rigid Foundations

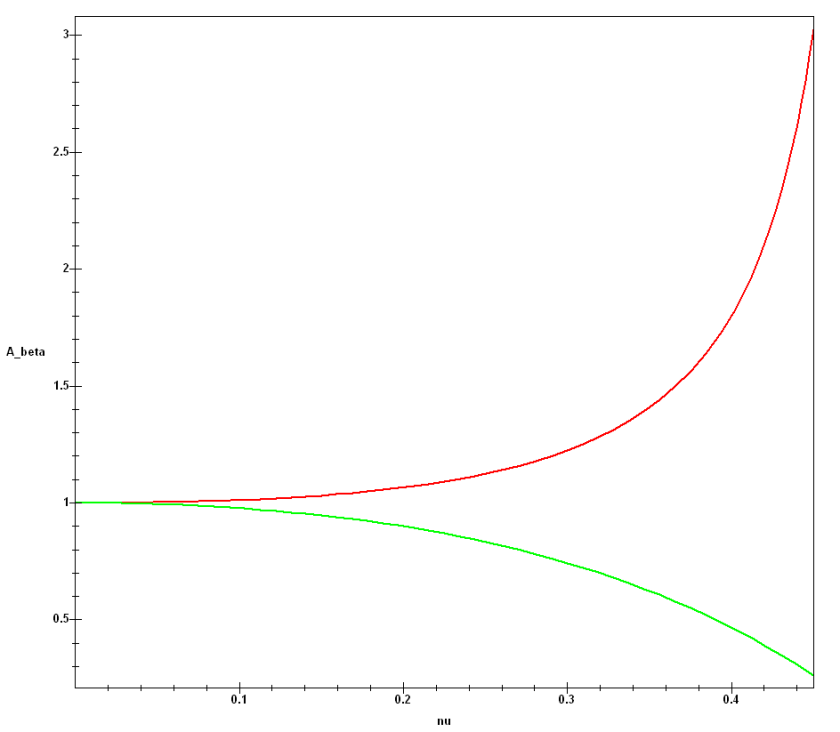

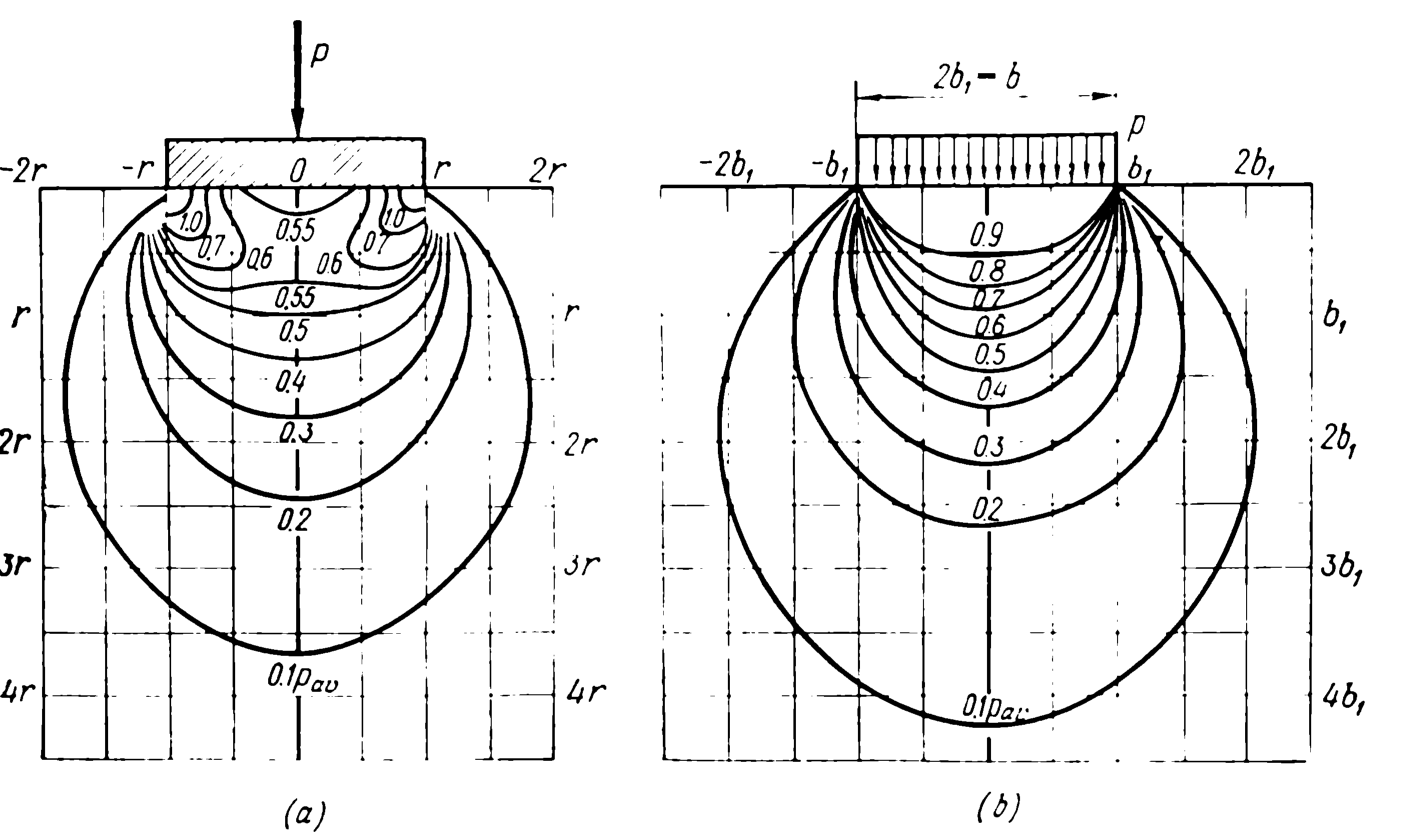

In Going Around in Circles for Rigid and Flexible Foundations we looked at stress distributions under circles (and strip loads for that matter.) The results can be summarised graphically below, from Tsytovich (1976).

View (a) shows a point load on a rigid foundation; it could be a distributed one too, as long as the load is concentric. In any case at the corners the vertical stress is infinite. In the real world one would expect the soil to go plastic long before that and the stresses to redistribute themselves, but we’ll stick with pure elasticity for the moment.

View (b) shows a distributed load on a flexible foundation. At the interface between the foundation and the soil the vertical stress is the load p, and it decreases the further you get away from the foundation. The strip load version of this is used to find the lower bound solution for bearing capacity in Lower and Upper Bound Solutions for Bearing Capacity.

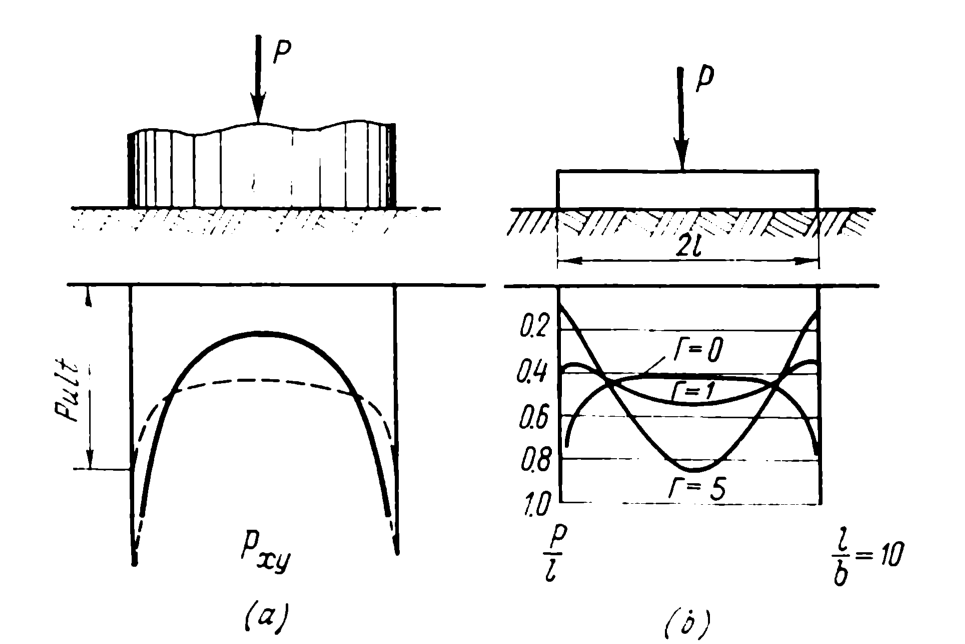

This is the state of affairs for foundations which are either perfectly flexible or perfectly rigid. The truth is that neither one of these extreme approximations is really true. This is illustrated in the figure below.

View (a) shows the rigid foundation with the stresses at the base of the foundation as they would be in elastic theory (solid line) and those with some “real world” plasticity thrown in (dashed line.)

If the rigid foundation is circular, for a semi-infinite, elastic homogeneous space, the stress distribution is as follows:

(1)

where

vertical stress in soil

uniform pressure on foundation. With rigid foundations we can have a point load P and obtain the same result as long as the load is at the centroid of the foundation

distance from centroid

radius of foundation

The relationship between a distributed load and a point load at the centroid is

(2)

For a rigid strip foundation,

(3)

where

distance from centreline of strip load

width of foundations

If we define, as is done in Figure 1, the half width of the foundation as

(4)

then Equation (3) becomes

(5)

The line load can be computed as follows:

(6)

View (b) shows a foundation with varying flexibility and the effect that has on stress distribution at the base. The flexibility of the foundation is described by the variable . We’ll discuss how that’s calculated later but

is a measure of the flexibility of the foundation.

is a totally inflexible (rigid) foundation

is a totally flexible foundation.

Before we get to that, let’s take a look at the other problem, that of a non-semi-infinite half space.

Non-Infinite Spaces and Flexible Foundations

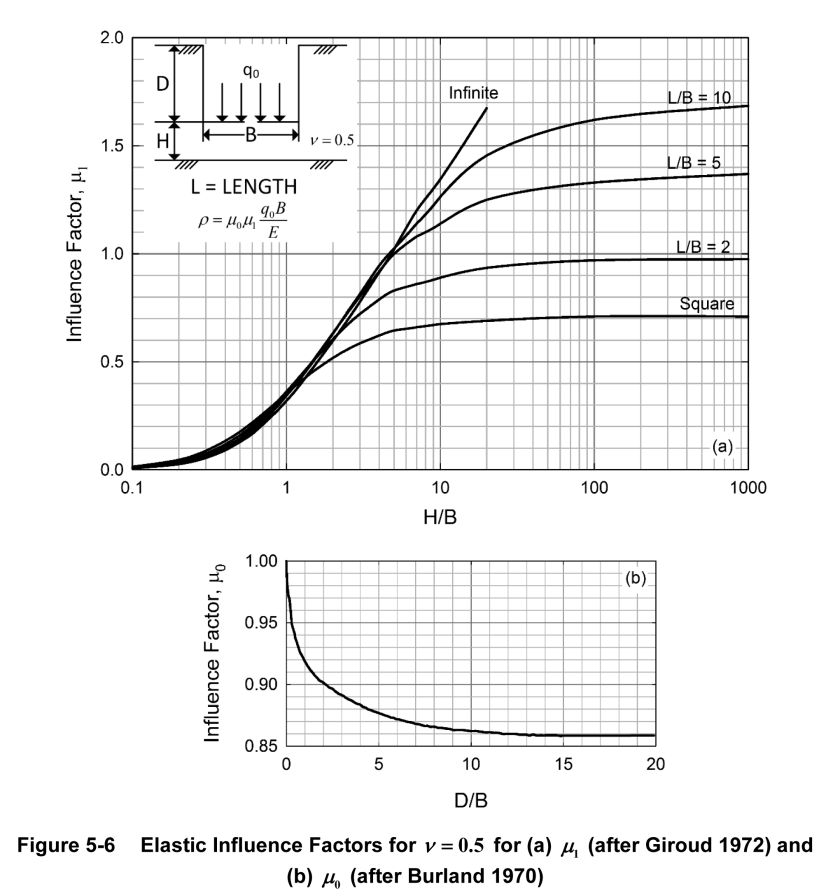

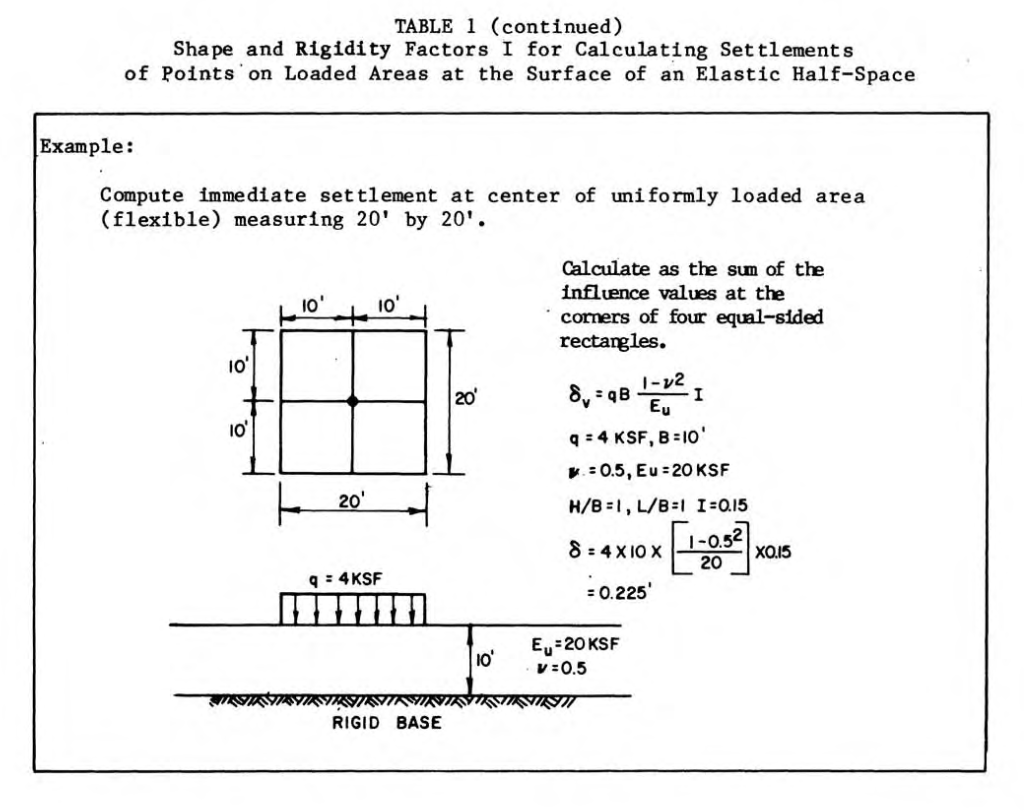

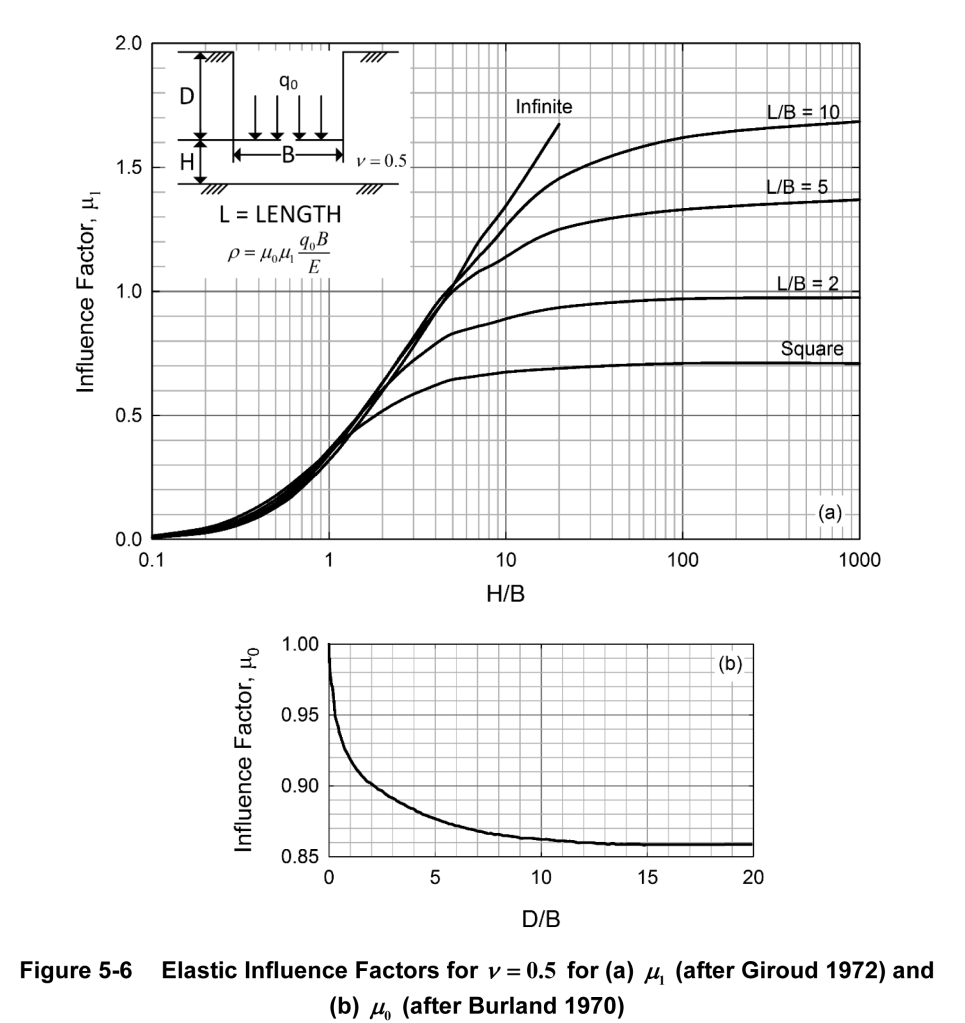

We’ll start with this problem, which is a progression from what we saw in Analytical Boussinesq Solutions for Strip, Square and Rectangular Loads and Going Around in Circles for Rigid and Flexible Foundations. Unfortunately the state of some of our usual sources forced us to make the treatment of this topic longer than we thought, so you can see it in our post Strange Results: The Case of Settlements on Non-Infinite Elastic Half Spaces and Flexible Foundations.

Non-Infinite Spaces and Rigid Foundations

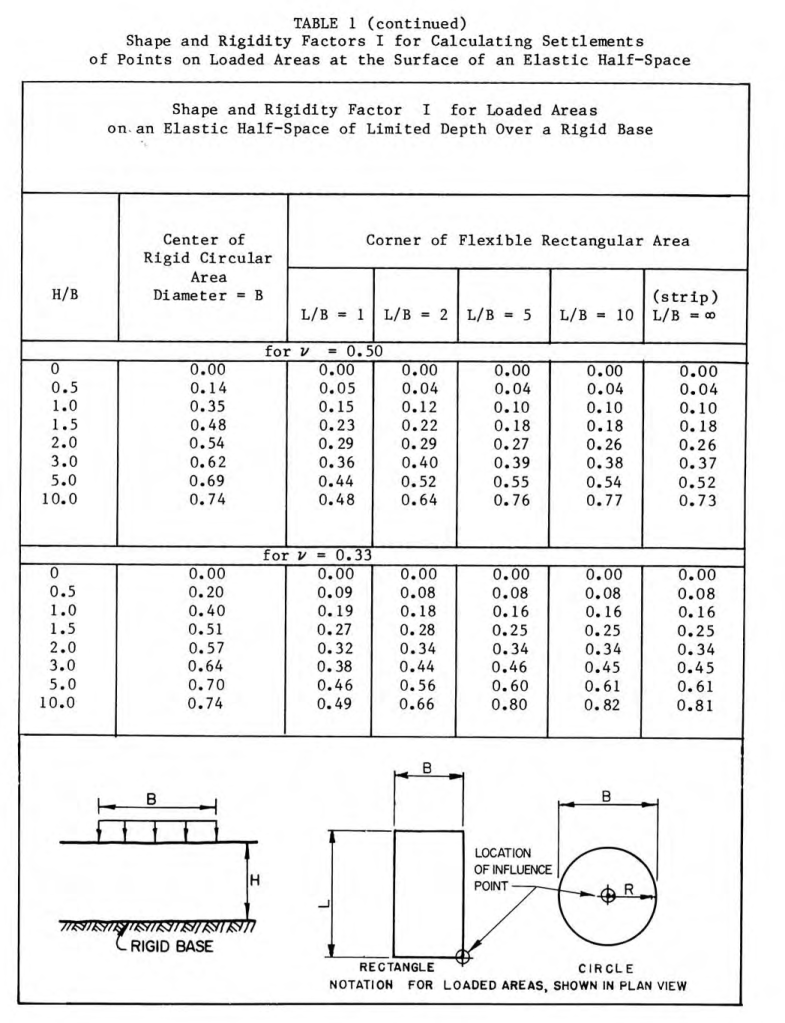

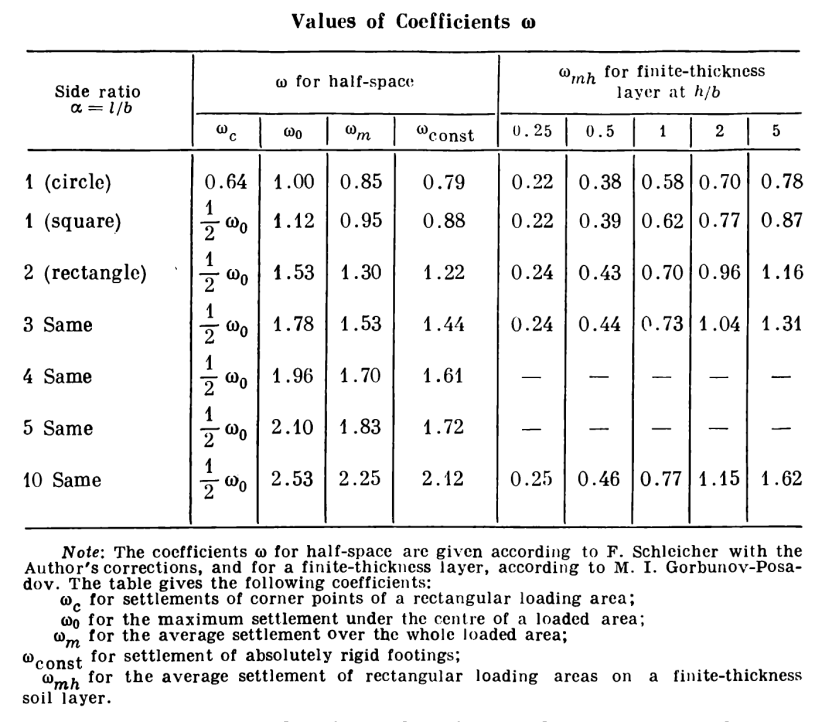

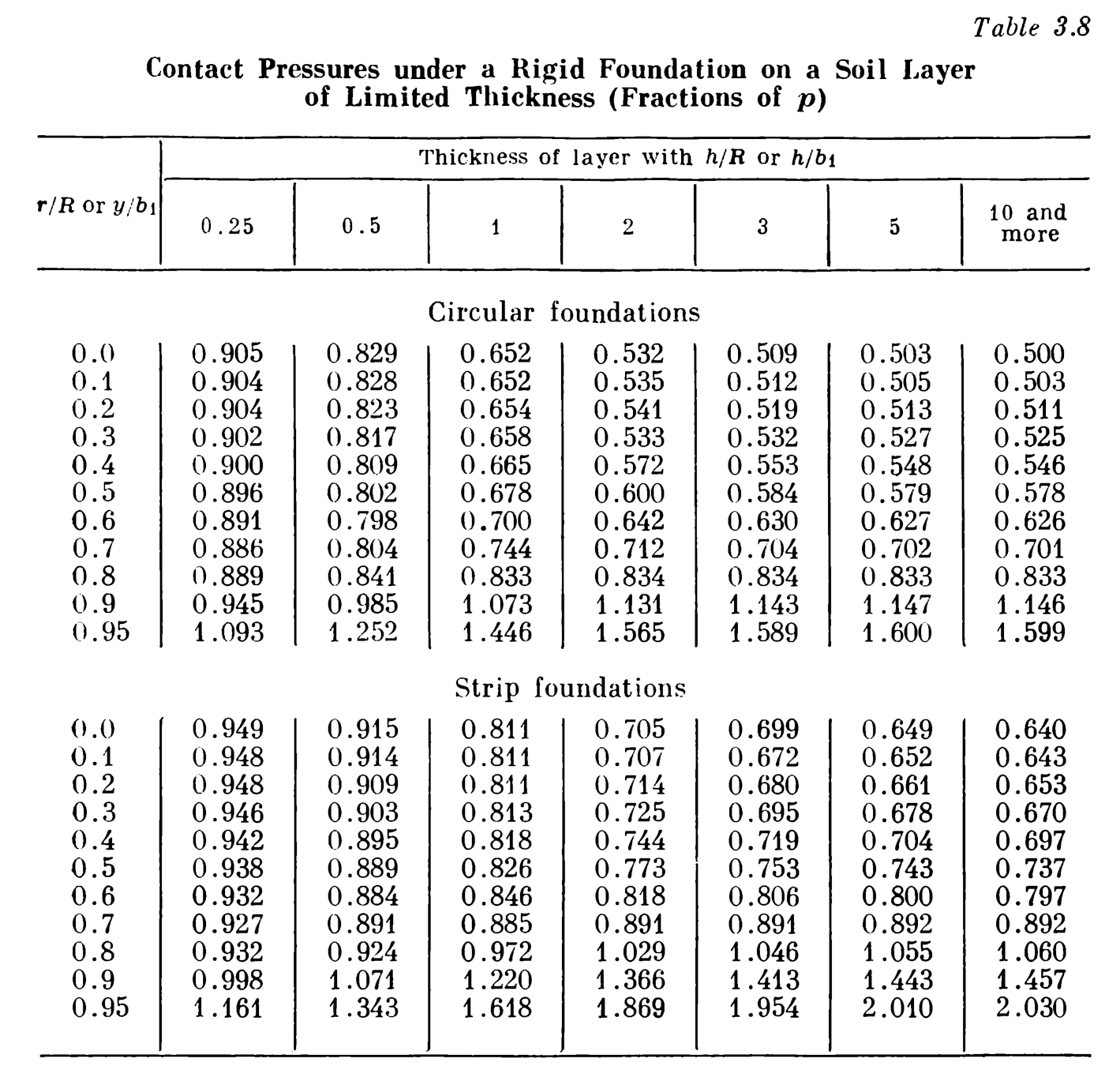

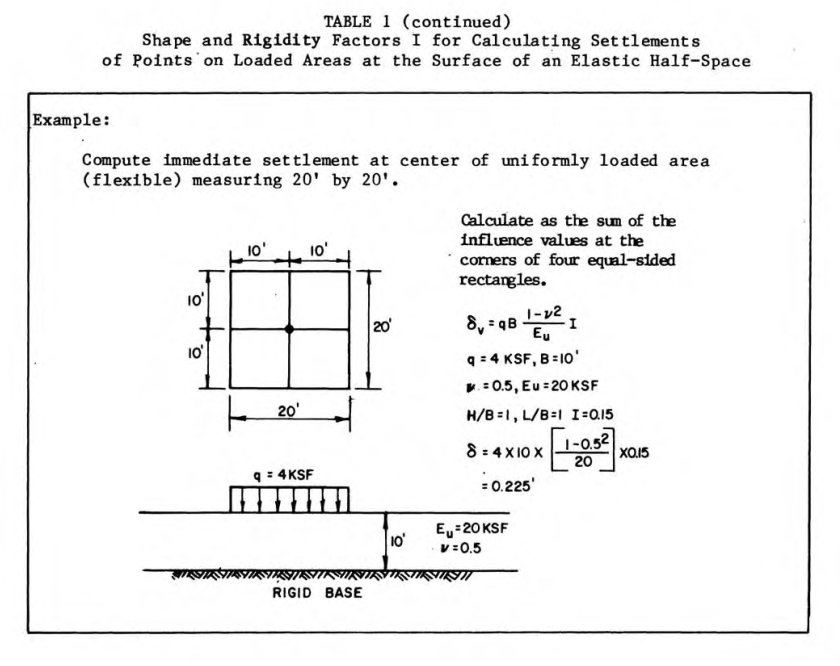

We now turn to the case of non-infinite spaces and rigid foundations. To deal with this problem we first present this table, from Tsytovich (1976):

The simplest way to show how this is used is through an example. Consider the case of a rigid strip load 3m wide and having a uniform pressure p = 50 kPa. Determine the stress distribution under the soil if the layer under it (until is encounters a hard layer) is 3 m.

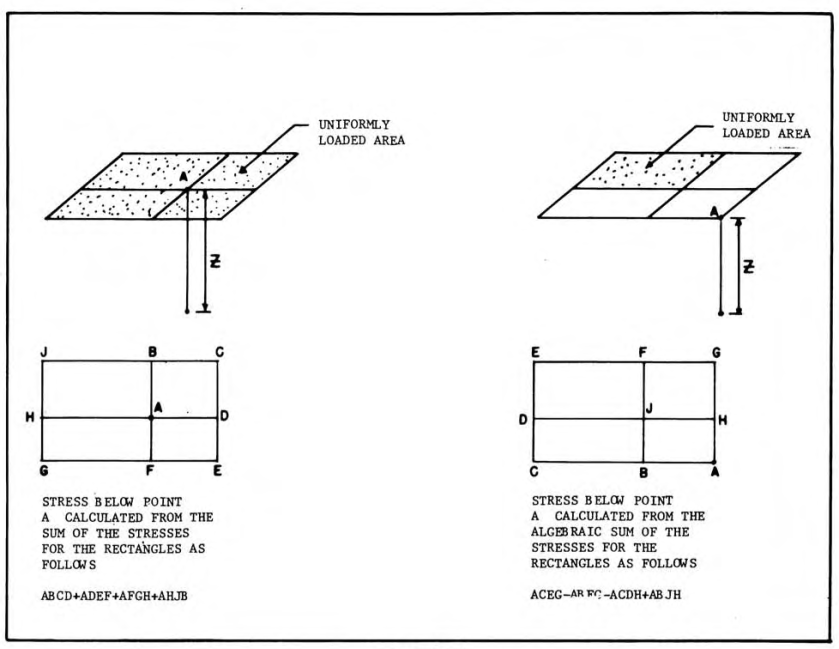

We start by considering Figure 1 and computing b1 = b/2 = 1.5m. We can thus say that h/b1 = 3/1.5 = 2. The ratio y/b1 varies from zero (at the centre of the foundation) to 0.95 (almost to the edge of the foundation, where the stress is infinite.) We compute the results for both the limited layer depth case (using Table 1) to the semi-infinite elastic space (using Equation 5) and tabulate the results below.

| y/b1 | y, m | Pressure Ratio (from chart) | Pressure, Limited Layer Depth, kPa | Pressure Ratio, Semi-Infinite Half-Space | Pressure, Semi-Infinite Half Space, kPa |

| 0 | 0 | 0.705 | 35.25 | 0.637 | 31.831 |

| 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.707 | 35.35 | 0.640 | 31.991 |

| 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.714 | 35.7 | 0.650 | 32.487 |

| 0.3 | 0.45 | 0.725 | 36.25 | 0.667 | 33.368 |

| 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.744 | 37.2 | 0.695 | 34.730 |

| 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.773 | 38.65 | 0.735 | 36.755 |

| 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.818 | 40.9 | 0.796 | 39.789 |

| 0.7 | 1.05 | 0.891 | 44.55 | 0.891 | 44.572 |

| 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.029 | 51.45 | 1.061 | 53.052 |

| 0.9 | 1.35 | 1.366 | 68.3 | 1.461 | 73.025 |

| 0.95 | 1.425 | 1.869 | 93.45 | 2.039 | 101.941 |

The effect of the limited layer depth is primarily to flatten the pressure distribution across the base of the foundation. The pressures are greater for the limited layer depth case in the centre and less towards the edges. Inspection of Table 1 will show that this effect will become more pronounced as the layer below the foundation becomes thinner.

It is interesting to note that, while the right column is very close to Equation (5), it is not identical. The solution is shown in detail in Elastic Solutions Spreadsheet.

Foundation Flexibility

We have discussed the foundation flexibility coefficient . A general formulation of this is

(7)

where

Young’s Modulus and Poisson’s Ratio of the soil

Young’s Modulus and Poisson’s Ratio of the foundation

Half length of foundation

Width of foundation

moment of inertia of foundation

If we substitute

(8)

then

(9)

Making common substitutions of yields

(10)

which we will use in our subsequent calculations.

At this point it’s probably worth noting that relative flexibility between foundation and soil is most important in mat foundations. These days most of these will be designed using finite element analysis or some other numerical method, and rightly so. If the flexibility is more than rigid () the distribution of the load will come into play, and it is seldom that a foundation is uniformly loaded. In the case of eccentrically loaded foundations, even with rigid foundations the load is redistributed.

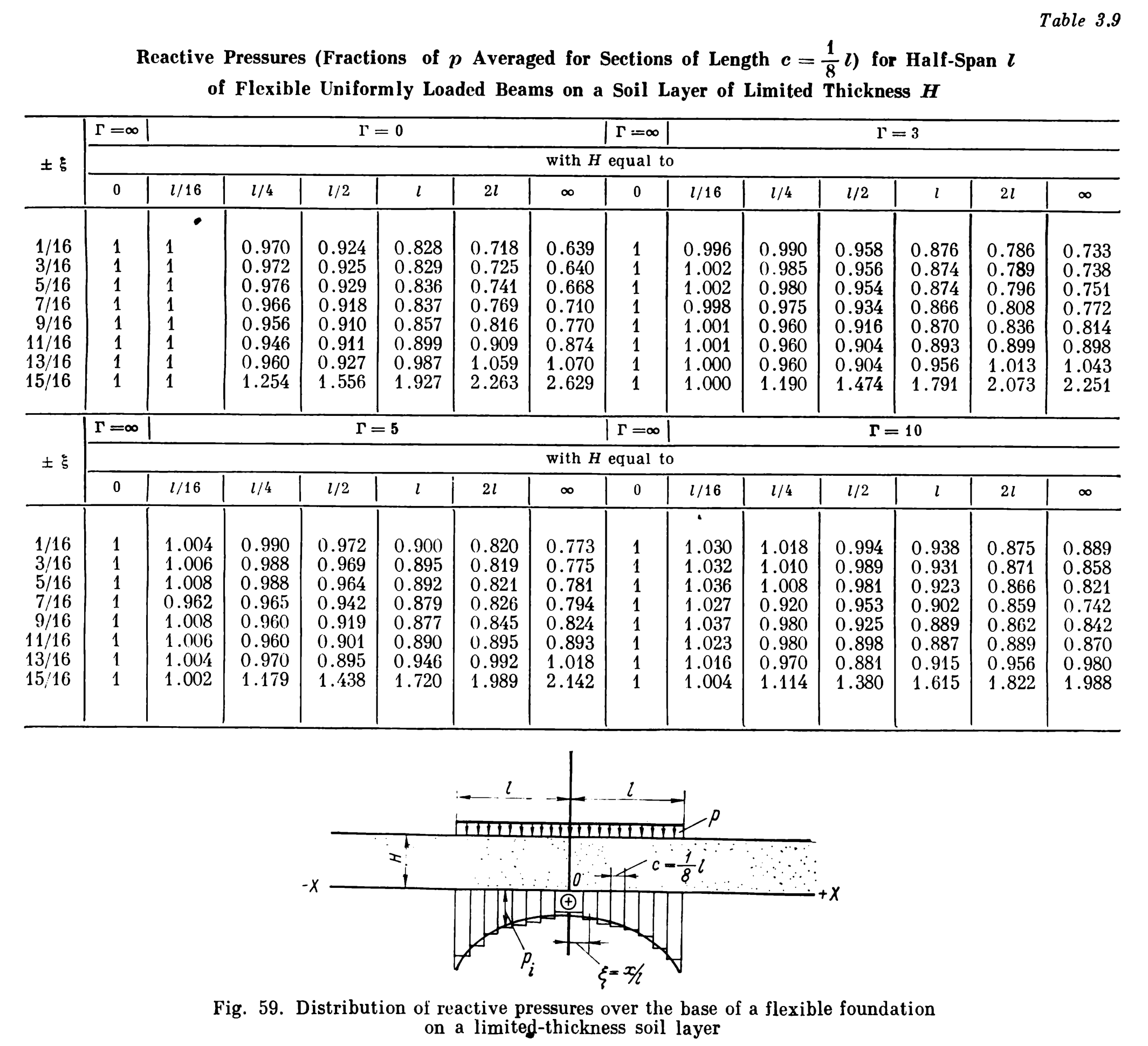

Nevertheless some kind of “back of the envelope” exercise is useful, not only for educational purposes but also for purposes of preliminary calculations. This is what we will do for stress distribution under a foundation with flexibility of . To begin we will present the following table, and as before we will illustrate its use with an example.

Let’s first dispense with the columns labelled . These are purely flexible foundations, the pressure on the soil is the same as the pressure on the foundation. The rest of these are for foundations with varying degrees of rigidity, from purely rigid foundations (

) to those where, as

increases, the flexibility of the foundation does also.

Since we are dealing with rectangular foundations, with a uniform pressure p the stress distribution is symmetrical about the centroidal axes of the foundation. The ratio is the fraction of the distance between the centroidal axis and the long end of the foundation, and in this case is divided into eight equal segments.

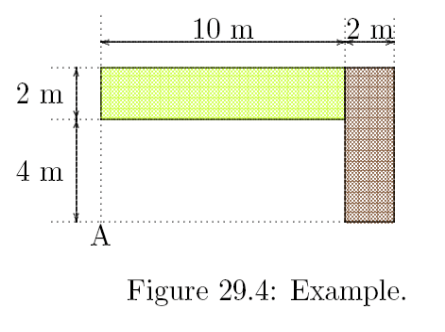

For an example, let us consider the foundation we looked at in Strange Results: The Case of Settlements on Non-Infinite Elastic Half Spaces and Flexible Foundations. It is shown below; the deflection result shown was discussed in that post.

The parameters necessary are as follows:

- The Young’s Modulus for concrete is approximately 720,000 ksf.

- We will assume that the foundation is 0.45′ (5.4″) thick for reasons that will become apparent.

- The half length

of the foundation is 10′, which means that, for Table 2,

.

- We will use the approximate value of

in Equation 10. Substituting,

, which avoids a great deal of interpolation.

Using Table 2 and making the appropriate substitutions yields the following results.

| Fraction of Pressure | Soil Vertical Reaction, ksf | |||||

| Rigid Foundation | Flexible Foundation | Rigid Foundation | Flexible Foundation | |||

| 0.0625 | 0.828 | 0.876 | 1 | 3.312 | 3.504 | 4 |

| 0.1875 | 0.829 | 0.874 | 1 | 3.316 | 3.496 | 4 |

| 0.3125 | 0.836 | 0.874 | 1 | 3.344 | 3.496 | 4 |

| 0.4375 | 0.837 | 0.866 | 1 | 3.348 | 3.464 | 4 |

| 0.5625 | 0.857 | 0.87 | 1 | 3.428 | 3.48 | 4 |

| 0.6875 | 0.899 | 0.893 | 1 | 3.596 | 3.572 | 4 |

| 0.8125 | 0.987 | 0.958 | 1 | 3.948 | 3.832 | 4 |

| 0.9375 | 1.927 | 1.791 | 1 | 7.708 | 7.164 | 4 |

From this result we note the following:

- As a practical matter, the results of the rigid foundation and that for

are not that different, but they are different from the flexible foundation (

.)

- The foundation is fairly thin to be considered “rigid.” One possibility is that the Young’s Modulus for the soil is very low. If we were to increase this by a factor of 10 to 200 ksf, we would achieve the same value for

with a foundation 1′ thick, which is still rigid relative to the soil.

- By the time

the foundation is approaching being purely flexible.

The solution is shown in detail in Elastic Solutions Spreadsheet.

Other Representations of Relative Rigidity

Although it would be nice to be able to determine the soil stress distribution under a foundation, for preliminary purposes it is probably not necessary since other methods of analysis must be done. Nevertheless the rigidity coefficient is potentially useful as a starting point to determine whether a foundation can be considered rigid or flexible.

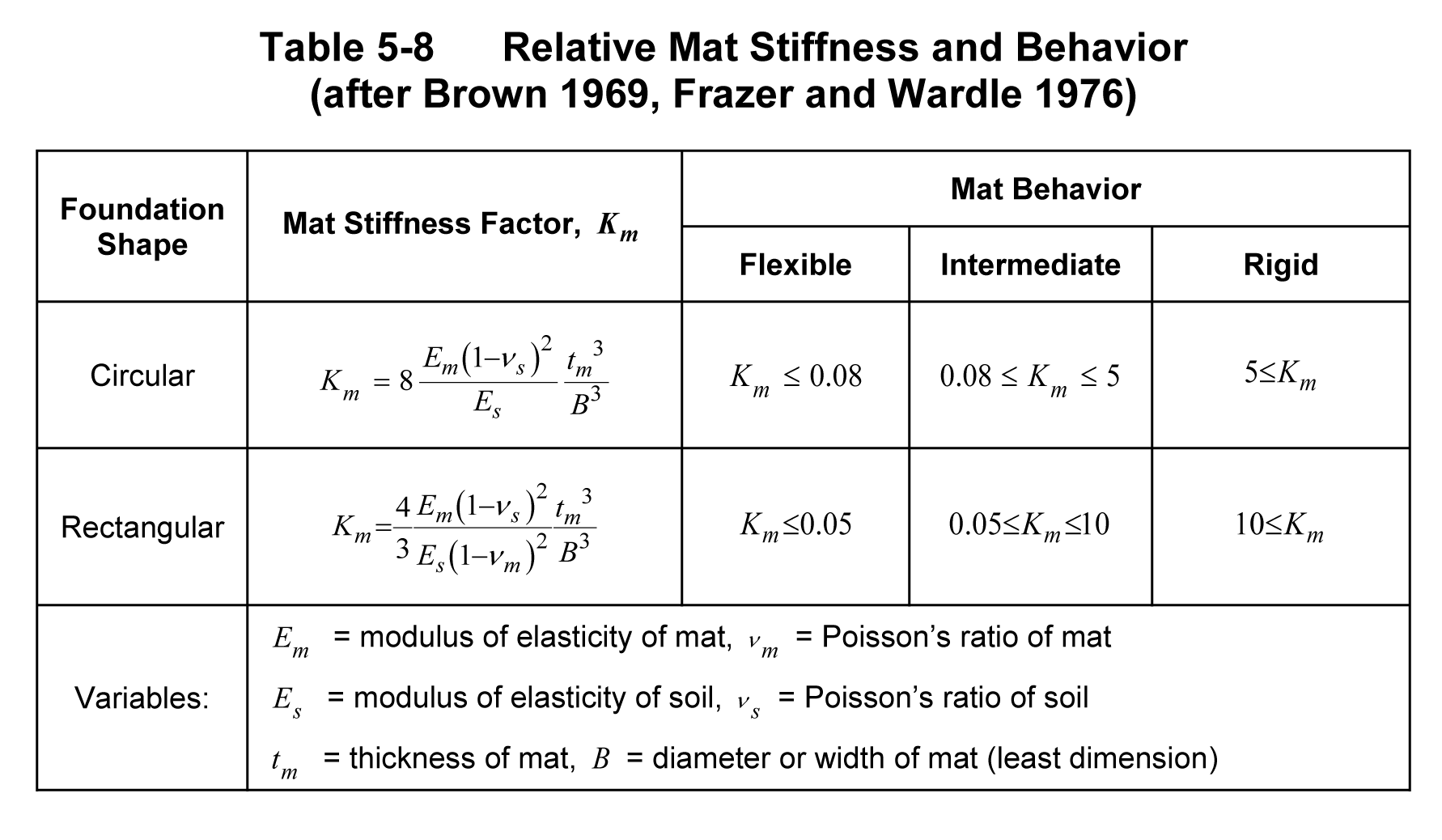

One such use is shown in NAVFAC DM 7.1:

A different notation for the stiffness factor is noted, but the similarity between the equations (especially that of the rectangular foundation) and Equation 10 is unmistakable. This is because there are common sources to both. For rectangular foundations the relationship between the two can be found by the equation

(11a)

or conversely

(11b)

Thus, considering rectangular foundations in Table 3, a foundation is flexible if , rigid if

, and intermediate between these values. For practical purposes, an intermediate foundation has

, it is rigid below this and flexible above.

One interesting difference is that Table 3 uses the short dimension B while Equation 10 uses the long half dimension l. For the square foundation in the example this isn’t a problem. However, it makes sense that the longer dimension drives the flexibility–and the bending moments–of the foundation.

In any case the behavior of the foundation can be affected by the relative rigidity of the mat and the soil under it. As NAVFAC DM 7.1 notes:

As indicated in Table 5-8, mats with low stiffness ratios can be considered completely flexible. Flexible mats will apply a relatively uniform pressure distribution, and the center, edges, and corners will settle differentially. Mats with high values of

* Or low values of* will act in a rigid manner and will tend to settle uniformly.

Two other factors need to be considered: the bending stresses in the mat (which is also affected by the reinforcement scheme) and the maximum stresses in the soil. The bending stresses in the mat needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis. Conventional wisdom may indicate that rigid mats would have larger bending stresses, but flexible mats are probably relatively thin and bending stresses may increase in these cases. The maximum stress in the soil immediately around the mat are higher with rigid mats than with flexible ones, especially along the edges. However the soil stresses that most influence the behaviour of the mat may be those which induce the largest settlements, such as those in, say, soft clay layers.