I recently received in inquiry from an organisation which has proposed a shallow foundation of an embankment. They used (wisely IMHO) an FEA analysis to estimate the settlement. The owner’s response was that, since their result was a little greater than Hough’s Method, and Hough’s method reputedly overestimates the settlements by a factor of 2, that the FEA analysis overestimated the settlements. They referred this person to my posts Getting to the Legacy of B.K. Hough and his Settlement Method and Closing the Loop (or at least trying to) on Hough’s Settlement Method, which is evidently about the only ongoing discussion of the topic around these days.

Both of these posts have two objectives: a) they attempt to trace the development of the method, both by Hough and those who came after, and b) to begin the journey to a resolution of the accuracy of the method. The problem with both of these is that the problem is simple to state but, because of the nature of the evidence, difficult to resolve. I’ll start with a brief review of these two objectives and then set forth a worked example (something that is admittedly lacking in my first two posts) to see how things work out. I’ll end with some thoughts on how to more accurately determine the values of C’, which is the core issue with this method.

The Method and Its Development: A Review

“The SPT is a dynamic test, while soil bearing capacity is a matter of statics, interpreting one in terms of the other is analogous to determining the bearing capacity of piles from pile driving formulas. Consequently, it is felt that attempts to present correlations between blow counts and bearing capacities of soils would be an oversimplification of a much too complex subject.” From Fletcher (1965)

“Hough’s Method” is not univocal; he presented it in two forms in Hough (1959) and Hough (1969). The governing equation is the same for both:

(1)

This equation is identical to Equation (3) of my post The Sorry State of Compression Coefficients except for the form of the variables. In some places equations like this are used for fine-grained soils; this is explained in Verruijt.

The basic problem is determining C’ and there are two difficulties with this:

- Hough changed the SPT N vs. C’ curves in the intervening decade between the two forms.

- We’re not informed what type of SPT hammer Hough used, or if/how he corrected them as we do now (there’s no evidence that he did.)

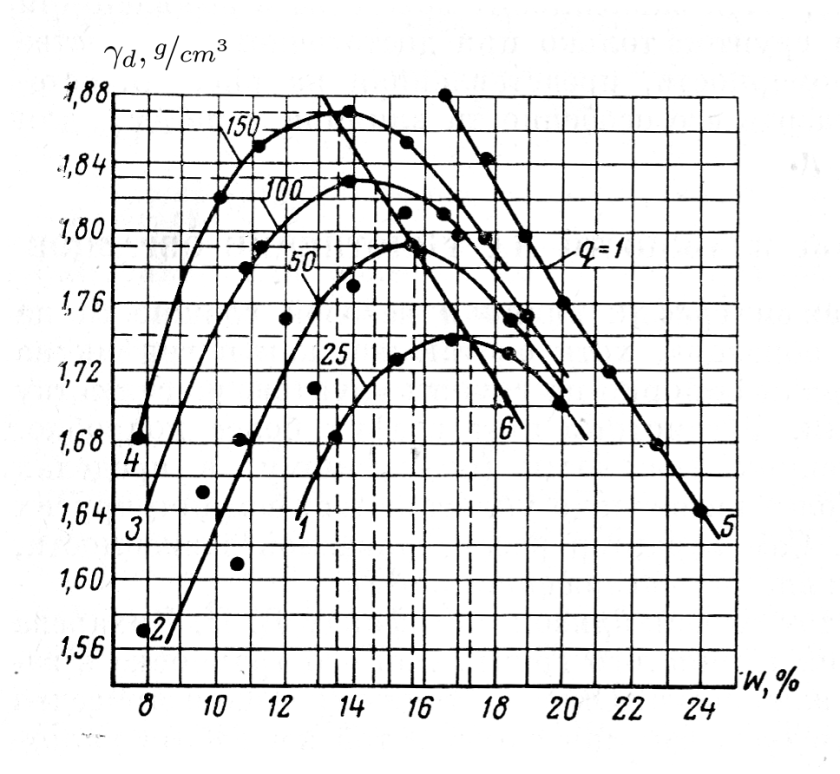

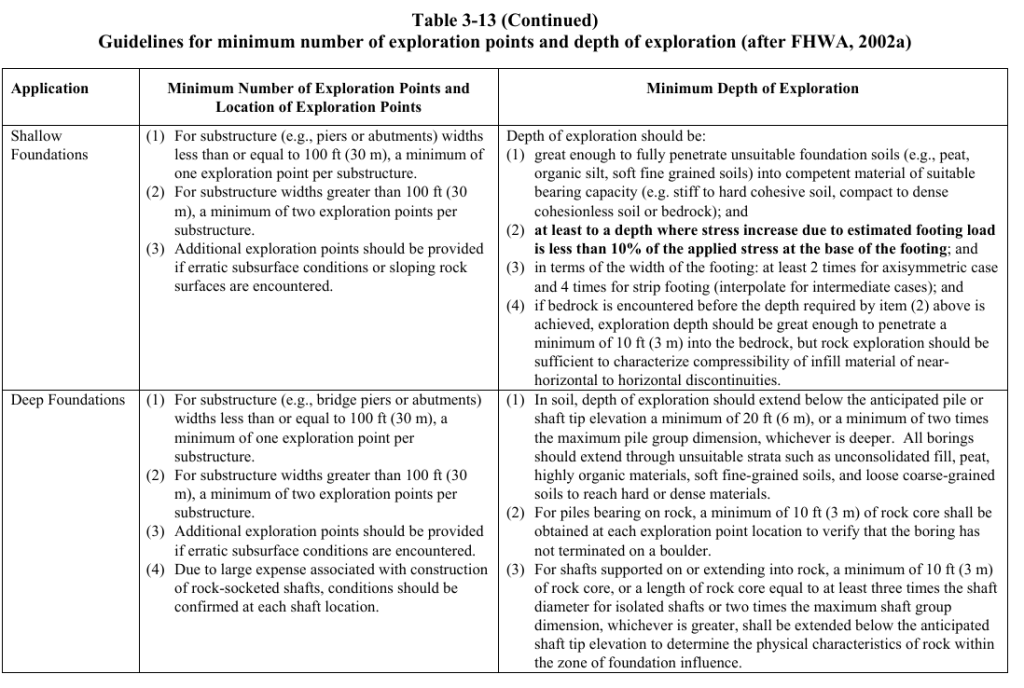

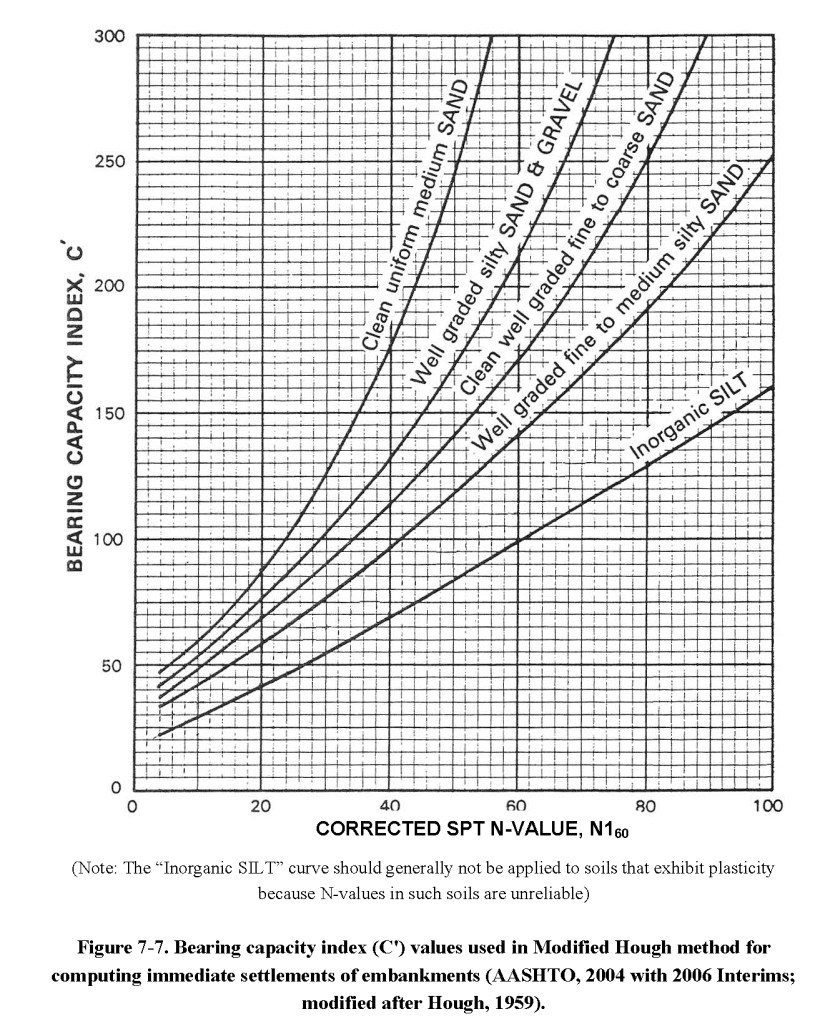

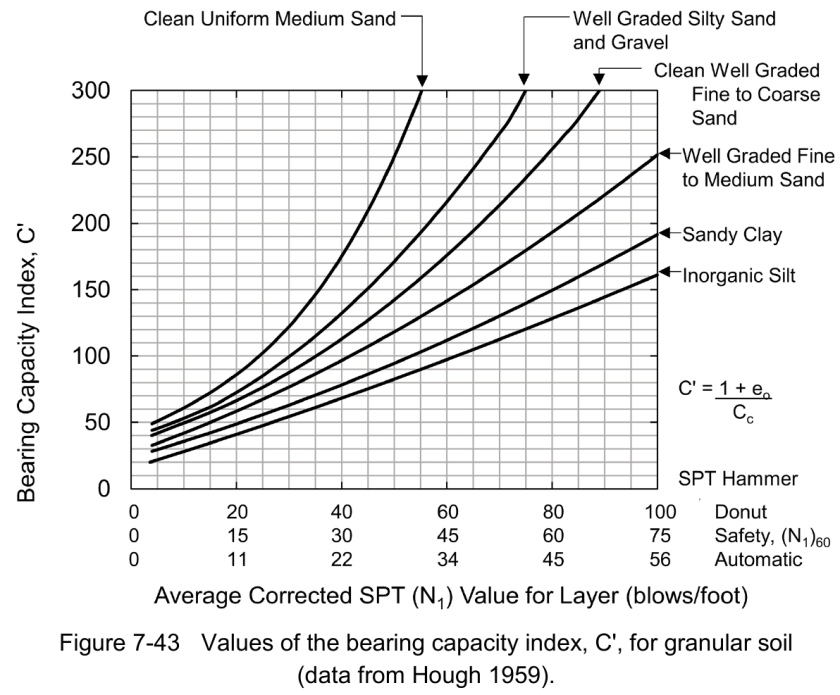

Let’s start with the first problem: the curves reproduced from the 1959 version (from the FHWA’s Soils and Foundations Manual) are here:

We’ll deal with the business of N160 shortly. There is no evidence that Hough meant to restrict his method to embankments.

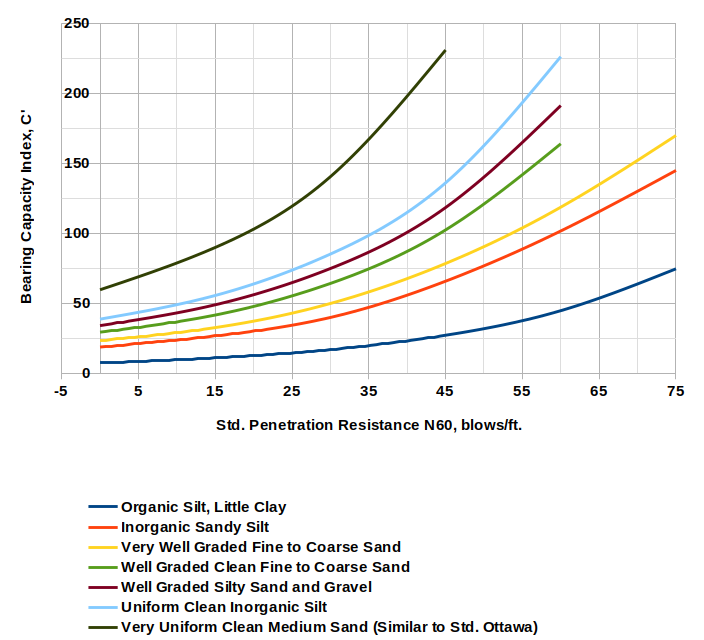

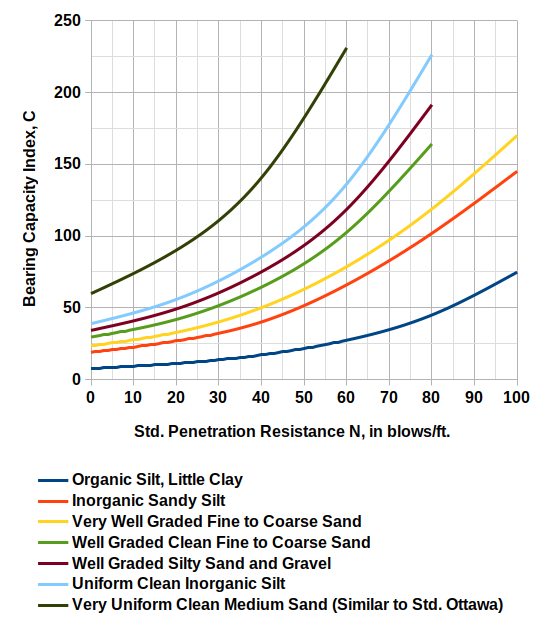

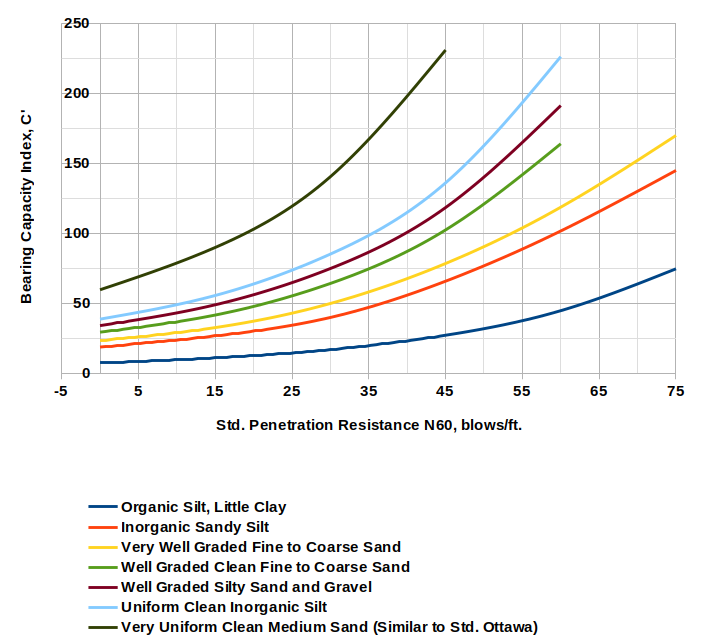

The chart from the 1969 version is reproduced below (my reproduction):

One of the more thoughtless things the FHWA has done in publishing this method is never presenting any equations for these curves, which are easily obtained using linear regression. I have done this and you can see them in Getting to the Legacy of B.K. Hough and his Settlement Method.

Obviously these sets of curves are not identical; the soil classifications he uses aren’t either, and there are five (5) curves in the 1959 version while there are seven (7) in the 1969 one.

Turning to the second problem, in neither of Hough’s original monographs is any kind of correction–mechanical or overburden–are mentioned. The FHWA has consistently added overburden correction. As far as mechanical correction is concerned, in Design and Construction of Driven Pile Foundations, 2016 Edition the FHWA has assumed (not unreasonably) that Hough obtained data from a donut hammer and their correction (which also includes overburden correction) looks like this:

In the same vein I shifted the x-axis of Figure 2 for N60 values as shown below.

Equations for these curves are included in Closing the Loop (or at least trying to) on Hough’s Settlement Method.

A Worked Example

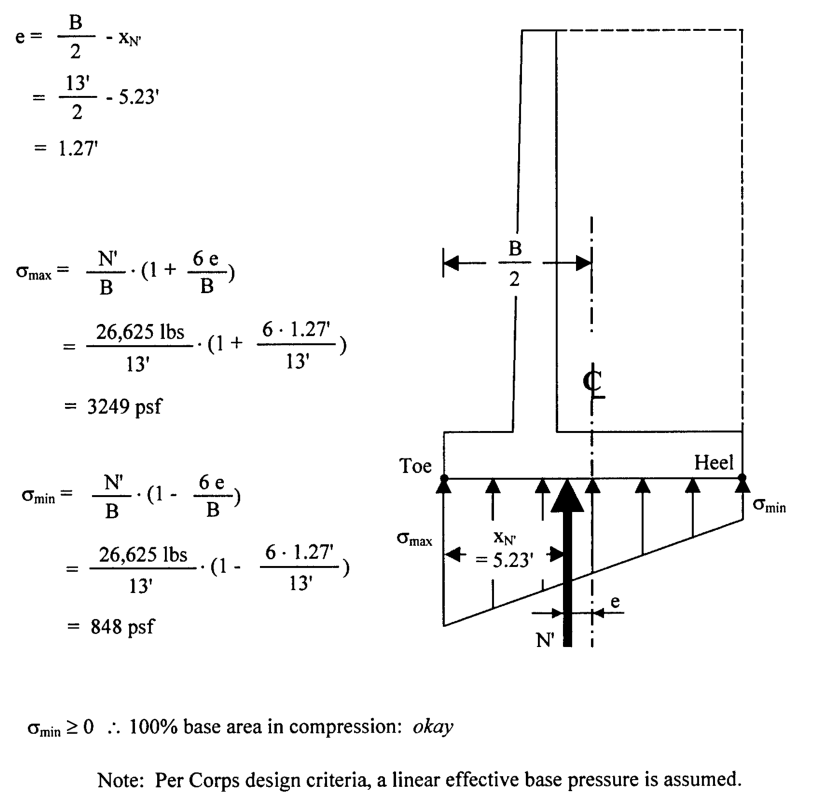

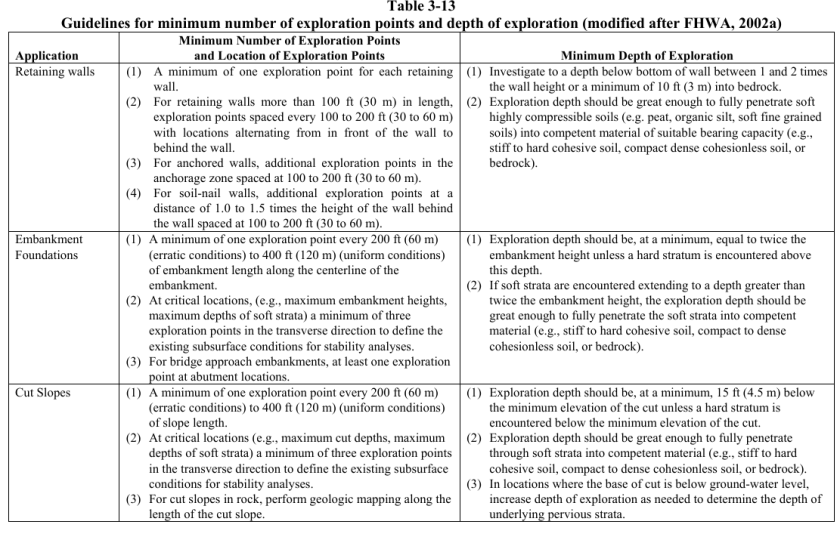

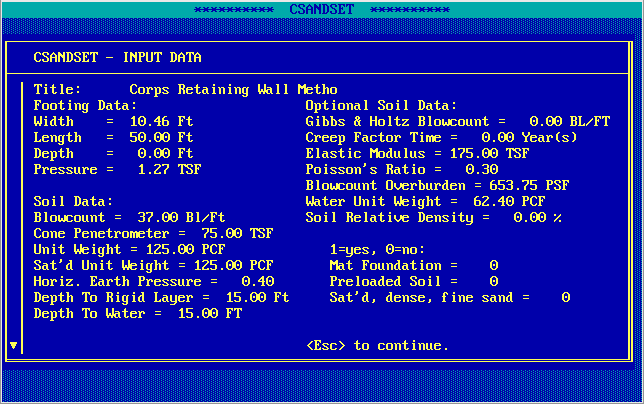

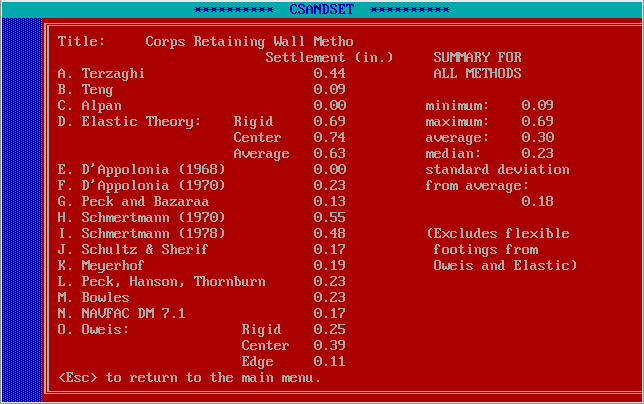

With that out of the way, the best way to illustrate the use of Hough’s Method is using a worked example, in this case a retaining wall foundation from A Simplified Method to Design Cantilever Gravity Walls. The diagram at the top of the page shows the foundation; the settlement calculations for a variety of methods (using the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ CSANDSET program) are given there. Let’s begin by reproducing those results below.

This program includes a fairly broad selection of methods, from elastic/theoretical ones to purely empirical ones. These methods are described in the program manual. While some of them may not be really applicable to this type of foundation, they show the wide variations of these methods, which suggests that there is not a consensus on computing these values.

Hough’s Method is not included. The detailed solution to the problem is contained in this spreadsheet. We assumed that the soil was well-graded fine to medium sand. There are four variations to the results, which are shown below:

| Variation on Hough’s Method | FHWA SFH Method | FHWA DPF Method | Closing the Loop (or at least trying to) on Hough’s Settlement Method proposal, no overburden correction | Closing the Loop (or at least trying to) on Hough’s Settlement Method proposal with N1(60) Values |

| Settlement, in. | 0.647 | 0.466 | 1.162 | 0.553 |

As has been documented widely, the results of Hough’s Method are generally above most of the methods used in CSANDSET, although in the case of Schmertmann’s Method (which has been widely disseminated) the difference is not so great. The largest of the Hough’s Method variations is the Closing the Loop (or at least trying to) on Hough’s Settlement Method proposal, so I ran this with the N1(60) values, which resulted in settlements between the two FHWA methods.

One thing I would caution about using an “academic” problem as an illustration is that the parameters–many of which are taken from “typical” values–may not be representative of what actually occurs in the field, and may yield less than satisfactory results, especially for methods with a strong empirical basis. I ran into this problem with Driven Pile Design: Three Methods of Analysis. On the other hand field results are specific to their location and may not be representative of soils that the geotechnical engineer can expect to encounter.

New Values of C’

I’m not sure how much progress has been really made in this discussion. First I summarised my last two posts on Hough’s Method and how it comes up with the value of the compression constant C’, which is an alternative method of using consolidation settlement techniques to estimate one-dimensional settlement. Then I applied this to an example. Both of these have some value but they don’t get to the heart of the issue: we need more reliable (or at least values of which we understand the source) of the compression constant C’.

One hallmark of many of the fixes for this method is the invocation of overburden correction, which (as we saw above) reduces the resulting settlement. Doing this reminds me of something my Computational Fluid Dynamics I professor put in his notes many years ago:

Also, a few words need to be said about how one should interpret results ensuing from a computational simulation. There are a couple of anecdotal-based observations that are often used to describe how to approach a calculated result: (1) Computed results are guilty until proven innocent, and (2) There’s nothing more dangerous than answers that look about right. These observations are related but have slightly different interpretations. The first says that newly computed results should always be viewed with aggressive skepticism. In other words, a CFD practitioner should never accept a computed result as “truth” or representative of Mother Nature until exhaustive means have been taken to ensure that the result is a “reasonable” approximation to reality. The second observation simply means that if a calculation gives results that are orders of magnitude different from those intuitively expected, then the results can usually be quickly judged as erroneous and there is work to do to find out why. The difficult part comes when a calculation gives results that are “close” to what was expected. Such an outcome often lulls the researcher and/or practitioner into thinking that “all is well” and there is no reason to continue scrutinizing the results. However, it is very possible that a “good” answer was obtained for the wrong reason.

Compression constant typical values aren’t exactly plentiful. This table, from Verruijt, is one I have put in my course materials for many years (for log10 formulations):

| Type of Soil | C’ |

| Sand | 20-200 |

| Silt | 10-50 |

| Clay | 4-40 |

| Peat | 1-10 |

Another tabulation comes from this source, converted to log10 values:

| Soil | Minimum C’ | Maximum C’ |

| Loess silt | 6.5 | 19.6 |

| Clay | 13.0 | 52.2 |

| Silts | 26.1 | 65.2 |

| Medium dense and dense sands | 65.2 | 87.0 |

| Sand with gravel | 108.7 | None |

Hough (1969) himself suggests another way forward. Referring to his table of compression coefficient parameters reproduced in Getting to the Legacy of B.K. Hough and his Settlement Method, we start by noting that he computes the values of Cc using the following equation:

(2)

Since the compression coefficient and constant are related in this way

(3)

we can combine these equations and compute the compression constant thus

(4)

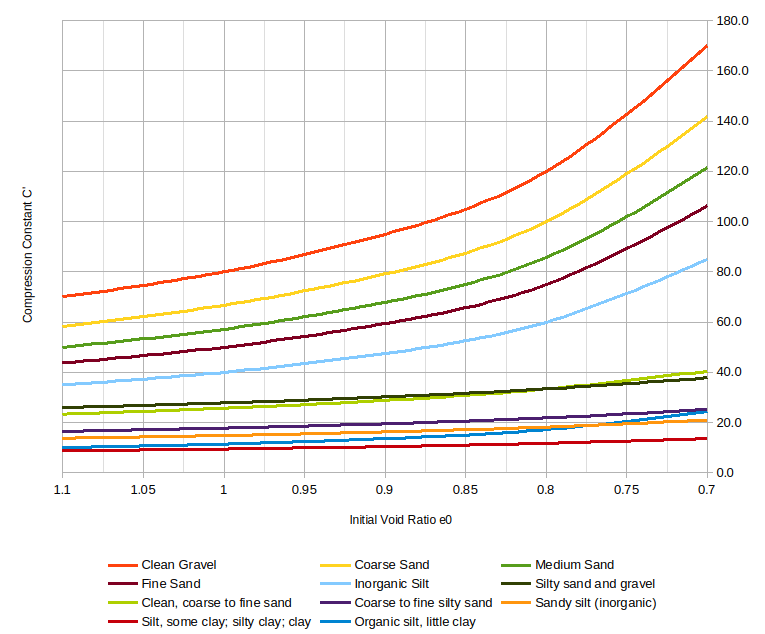

Doing this for Hough’s values of a and b (and one should be aware of the caveats he puts on values of b) for a range of void ratios yields the following tabular result:

| Hough’s Coefficients | Initial Void Ratio e0 (first row) Values of C’ (rows that follow) | ||||||

| Soil Type | a | b | 1.1 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Clean Gravel | 0.05 | 0.5 | 70.0 | 80.0 | 95.0 | 120.0 | 170.0 |

| Coarse Sand | 0.06 | 0.5 | 58.3 | 66.7 | 79.2 | 100.0 | 141.7 |

| Medium Sand | 0.07 | 0.5 | 50.0 | 57.1 | 67.9 | 85.7 | 121.4 |

| Fine Sand | 0.08 | 0.5 | 43.8 | 50.0 | 59.4 | 75.0 | 106.3 |

| Inorganic Silt | 0.1 | 0.5 | 35.0 | 40.0 | 47.5 | 60.0 | 85.0 |

| Silty sand and gravel | 0.09 | 0.2 | 25.9 | 27.8 | 30.2 | 33.3 | 37.8 |

| Clean, coarse to fine sand | 0.12 | 0.35 | 23.3 | 25.6 | 28.8 | 33.3 | 40.5 |

| Coarse to fine silty sand | 0.15 | 0.25 | 16.5 | 17.8 | 19.5 | 21.8 | 25.2 |

| Sandy silt (inorganic) | 0.18 | 0.25 | 13.7 | 14.8 | 16.2 | 18.2 | 21.0 |

| Silt, some clay; silty clay; clay | 0.29 | 0.27 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 10.4 | 11.7 | 13.6 |

| Organic silt, little clay | 0.35 | 0.5 | 10.0 | 11.4 | 13.6 | 17.1 | 24.3 |

Graphically this is what it looks like:

Although I would be reluctant to reconstruct the method based on this, it shows one important thing: there’s more than one way to get to these constants. If we want to have a method for consolidation settlement type solutions for cohesionless soils, we need to pursue all of the following:

- SPT correlations, based on current practice for correcting and applying the results.

- CPT correlations. Although not appropriate in all stratigraphies (what method is?) CPT is very useful and more consistent than the SPT in those stratigraphies where it can be applied successfully.

- Basic soil properties such as void ratio, relative density and unit weight. This suggests lab tests on undisturbed samples; the problem here is that getting undisturbed samples of cohesionless materials into a consolidation testing machine is easier said than done.

It’s also possible to use tests such as the pressuremeter and dilatometer, but these would only be meaningful in places where they are commonly used.

Doing all of these things would advance our understanding of the settlement of shallow foundations and give us more meaningful comparison with finite element methods.

Unlinked References

- Fletcher, G.F.A. (1965) “Standard Penetration Test: Its Uses and Abuses.” Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Division : Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers. Vol. 94 No. 4, pp. 67-75. It is interesting to note that Fletcher cites Hough’s First Edition of Basic Soils Engineering, while Hough (1969) cites Fletcher (1965).

- Hough, B.K. (1959). “Compressibilty as the Basis for Soil Bearing Value,” Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Division, ASCE, Vol. 85, Part 2.

- Hough, B.K. (1969). Basic Soils Engineering. Second Edition. New York: Ronald Press Company.