One of the things that gets covered (if not very thoroughly) in Soil Mechanics is how friction is developed in soils. An analogy is made with the classic “block on a surface” problem we see in Statics, but the tie-in isn’t as strong as one would like.

The fact is that, for purely cohesionless soils, the friction between the particles and the friction between the surface and the block is basically the same Coulombic friction. As is usually the case in soil mechanics, how that actually plays out in soil properties has many complexities, but then again surface friction isn’t a simple or straightforward property in and of itself.

Another part of the problem is that, in Statics, friction isn’t taught with geotechnical considerations in mind, especially these days. This is a pity, not only for those of us in the geotechnical community but for those who work with granular materials on a production or use basis.

This is a brief treatment of the subject, basing the development of the topic from that in Movnin and Izrayelit (1970), which comes closer to relating the two quantities we see to define friction: the friction angle and the friction coefficient.

The Basics of the Friction Coefficient and Angle

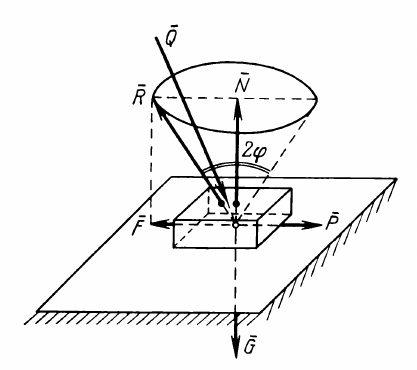

Surface friction comes from the rubbing of two surfaces together, as shown at the right. We see the three forces with which the two surfaces interact: the normal force N, the resulting friction force F and the resultant of the two R. We also see that the addition of lubricant is important in that it separates the two surfaces and reduces the effect of the asperities on each other, something that contractor and engineer alike frequently overlook in both the maintenance and performance evaluation of the equipment.

The normal and frictional forces resisting the relative motion of the two surfaces is related by the equation

F = fN (1)

With granular materials, the main difference is that the surfaces of the particles aren’t straight at all but they do rub up against each other, the asperities on the particle surface contributing to the mutual resistance of the particles. Although water acts to a limited extent as a lubricant, its largest effect is the buoyant effect on the intergranular (effective) stress, as shown below.

Returning to the first diagram, without any mutual pressure of the surfaces (the normal force N) there is no friction force F tangential to the surface. Again in soil mechanics purely cohesionless (granular) soils have no frictional strength unless weight or other pressure is applied to them.

Now let us consider the diagram at the right. The normal force N exerted by the surface on the block (caused by the force exerted on the block Q) and the frictional force F (caused by the force P which attempts to move the block) add vectorially to a resultant R, which in turn has an angle with the normal force N. The geometry of the forces and Equation (1) relate the angle to the friction factor as

f = F/N = tan (φ) (2)

Cone of Friction

Although F and N are related through both Equations (1) and (2), in reality F cannot exist without some tangential force pushing the block. This is the force P which is attempting to push the block along the plane. As P increases F increases until we get to a point where we have impending motion, beyond which the block moves and begins to accelerate. The value of f or φ when impending motion turns into actual motion is when we reach the ultimate value of f or φ, which we will designate as f0 or φ0.

These form a “cone of friction.” This cone of friction can be seen in the diagram at the left. As long as F < f0 N (or F < tan (φ0) N) and the resultant Q of N and F is within the cone, the block is motionless. Beyond that point it moves, and the coefficient of friction in motion can be different (usually smaller) than the coefficient of friction at the point of impending motion.

It is here that we can relate the friction factor f and the angle of friction φ can be related to each other and to concepts familiar to geotechnical people. When we construct the Mohr-Coulomb diagram, we define a failure envelope of legal stress states (within the envelope) and illegal stress states (outside the envelope.) We can see all of these with the failure function below. When the failure function is negative (1), we are within the envelope and failure does not take place. When the failure function is zero (2), we have impending failure. When the failure function is positive (3), we have failure and an illegal stress state.

Three-dimensional envelopes are certainly common in geotechnics, especially in finite elements. An example of this is shown below.

Determining the Friction Factor or Angle

To determine the friction angle, one simple way is to start with a block and a level surface and then raise the angle of the surface until the block moves. Such an apparatus is shown at the left.

As the angle α increases the direction of the weight G relative to the surface changes in can be divided into two parts: the normal force G2 and the tangential force G1. The latter will move the block down but it is resisted by the friction force F, which will resist until G1 > F0, at which point the block will start to move down the slope at a constant acceleration. By noting the angle at which this takes place, both f0 or φ0 = α0 can be determined. The math for this is similar to the level surface and block.

The geotechnical counterpart to this is the angle of repose. Suppose we allow a small stream of sand to drop on a surface. Over time the sand will build up into a conical pile with the surface at an angle to the flat surface the sand is streamed onto. This angle is referred to as the angle of repose. In theory the angle of repose is equal to the friction angle of the soil, although with the usual complexities of geotechnics this isn’t always the case. There are clean sands with which we can use the angle of repose to estimate the internal friction angle of the soil. When I was teaching at UTC, some of the students were working on the ASCE MSE Wall project and needed a friction value for the sand being used in the box. While they were looking at direct shear or triaxial testing, I suggested using the angle of repose to get a “ballpark” value. They did this and it was helpful.

Some Comments

- The use of the angle of friction has fallen out of favour in engineering education, which is one reason why it is difficult to relate friction as taught in Statics to friction as used in geotechnical engineering. That wasn’t always the case; one example from the early twentieth century is Tapered Keys and Their Use In Vulcan Hammers.

- Hopefully this treatment of the subject will be useful to students to help them relate the concept of friction in statics to that in geotechnical engineering.