This is the beginning of what hopefully will be an enlightening series on elasticity and plasticity, primarily as it appears in finite element code. It is taken from a number of sources, including (but not limited to) Owen and Hinton (1980), Smith and Griffiths (1988) and Cook, Malkus and Plesha (1989.) Although finite element code has certainly advanced, the basics are still the same, especially with elasticity (plasticity is another matter.) More information on finite element analysis in geotechnics (with a link to Owen and Hinton) can be found here.

The basic elasticity relationship is familiar to engineers and can be stated as follows:

(1)

(1)

where

stress

stress Young’s modulus, or modulus of elasticity

Young’s modulus, or modulus of elasticity strain

strain

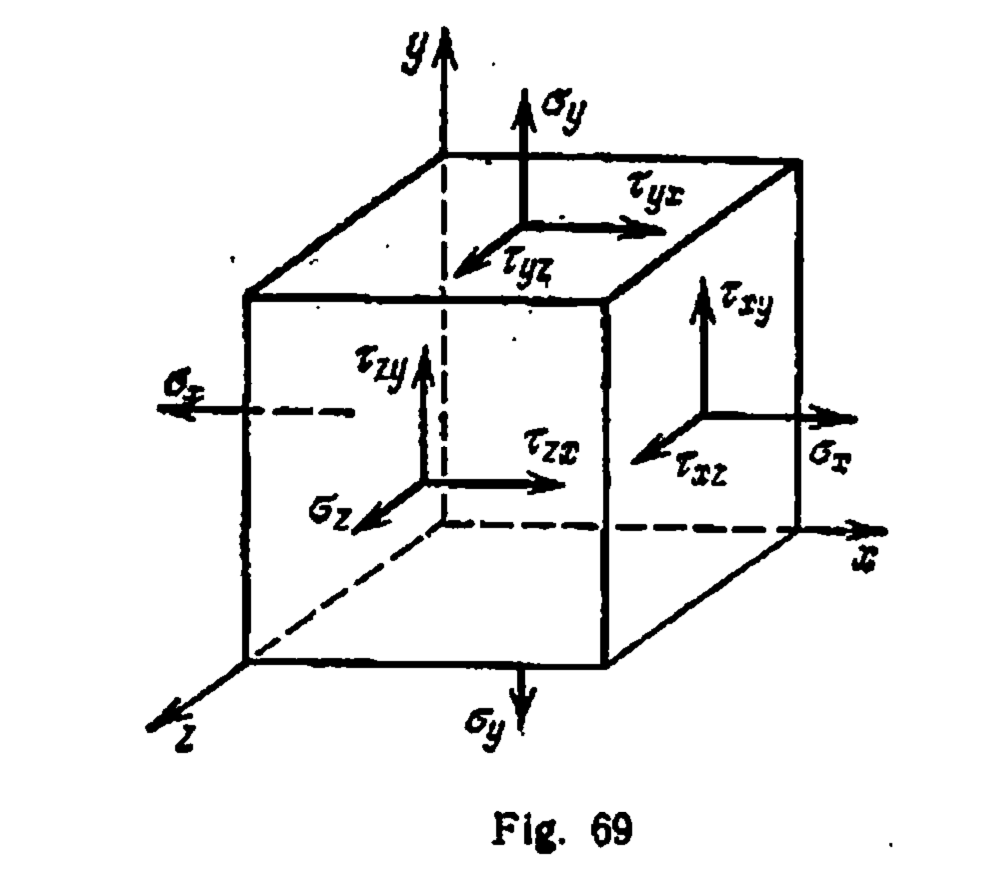

It can be used in one-dimensional analyses such as tension and compression testing; we’ll come back to that later. But real problems are always in three dimensions in one way or another. Let’s start by considering an infinitesimal element (these are discussed in Verruijt) that looks like the one in Figure 69. There are many ways of looking at this element. For one thing, it is in static equilibrium, which means that the stresses can be changed along with the coordinate system and the results still be in static equilibrium. Related to this is the fact that there is one coordinate system at which point the shear stresses vanish and the three normal stresses that are left are the principal stresses; this is discussed here.

These, however, are not our main interest here. Our main interest is how the element deforms under stress. For now we will restrict our discussion to elastic, path-independent stresses. We will rewrite Equation (1) is a slightly different form:

(2)

(2)

Now both  and

and  are vectors; you can see the multiple stresses in Figure 69. We use the notation

are vectors; you can see the multiple stresses in Figure 69. We use the notation  because the modulus of elasticity

because the modulus of elasticity  is a material property and thus is a part of the elasticity matrix

is a material property and thus is a part of the elasticity matrix  .

.

In any case, when the actual vector and matrices are substituted into Equation (2), for three-dimensional problems such as shown in Figure 69 the equations look like this:

![\left[\begin{array}{cccccc} {\frac{{\it E}\,\left(1-\nu\right)}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & {\frac{{\it E}\,\nu}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & {\frac{{\it E}\,\nu}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{{\it E}\,\nu}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & {\frac{{\it E}\,\left(1-\nu\right)}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & {\frac{{\it E}\,\nu}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{{\it E}\,\nu}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & {\frac{{\it E}\,\nu}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & {\frac{{\it E}\,\left(1-\nu\right)}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(1-2\,\nu\right)}} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & {\frac{{\it E}\,\left(1-\nu\right)}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(2-2\,\nu\right)}} & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & {\frac{{\it E}\,\left(1-\nu\right)}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(2-2\,\nu\right)}} & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & {\frac{{\it E}\,\left(1-\nu\right)}{\left(1+\nu\right)\left(2-2\,\nu\right)}} \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c} \epsilon_{{x}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\epsilon_{{y}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\epsilon_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\gamma{}_{{\it xy}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\it \gamma}_{{\it yz}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\it \gamma}_{{\it zx}} \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{c} \sigma_{{x}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\sigma_{{y}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\sigma_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it xy}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it yz}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it zx}} \end{array}\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bcccccc%7D+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%281-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%282-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%282-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cit+E%7D%5C%2C%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7B%5Cleft%281%2B%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Cleft%282-2%5C%2C%5Cnu%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cepsilon_%7B%7By%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cgamma%7B%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D%3D%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+%5Csigma_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7By%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D+&bg=ffffff&fg=777777&s=0&c=20201002) (3)

(3)

It should be immediately apparent that there are many repetitious quantities. There are many ways of dealing with the problem. For this analysis we will substitute Lamé’s constants, which are

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

where  is Poisson’s Ratio and

is Poisson’s Ratio and  is the shear modulus of elasticity. The latter is very useful in soil mechanics (which can be seen, for example, here) and in fact Equation (4) can be restated as follows:

is the shear modulus of elasticity. The latter is very useful in soil mechanics (which can be seen, for example, here) and in fact Equation (4) can be restated as follows:

(6)

(6)

At this point we need to observe one important thing: no matter whether you use Equation (4) or (6), the Lamé constant  blows up (or becomes singular, as we say in polite circles) when

blows up (or becomes singular, as we say in polite circles) when  . Materials where this is the case (such as very soft clays) are in reality fluids, the normal stresses become equal and the shear stresses only appear when the fluid moves. Avoiding this condition is one of the challenges of geotechnical finite element analysis.

. Materials where this is the case (such as very soft clays) are in reality fluids, the normal stresses become equal and the shear stresses only appear when the fluid moves. Avoiding this condition is one of the challenges of geotechnical finite element analysis.

It’s also worth noting that this is the same Lamé who came up with the theory behind shrink fits that is important with Vulcan hammers.

In any case, if we apply Equations (5) and (4) or (6), we obtain the following:

![\left[\begin{array}{cccccc} {\frac{\left(1-\nu\right)\lambda}{\nu}} & \lambda & \lambda & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}\lambda & {\frac{\left(1-\nu\right)\lambda}{\nu}} & \lambda & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}\lambda & \lambda & {\frac{\left(1-\nu\right)\lambda}{\nu}} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & G & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & G & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & G \end{array}\right] \left[\begin{array}{c} \epsilon_{{x}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\epsilon_{{y}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\epsilon_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\gamma{}_{{\it xy}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\it \gamma}_{{\it yz}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\it \gamma}_{{\it zx}} \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{c} \sigma_{{x}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\sigma_{{y}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\sigma_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it xy}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it yz}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it zx}} \end{array}\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bcccccc%7D+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Clambda%7D%7B%5Cnu%7D%7D+%26+%5Clambda+%26+%5Clambda+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Clambda+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Clambda%7D%7B%5Cnu%7D%7D+%26+%5Clambda+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Clambda+%26+%5Clambda+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Clambda%7D%7B%5Cnu%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+G+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+G+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+G+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D++%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cepsilon_%7B%7By%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cgamma%7B%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D%3D%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+%5Csigma_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7By%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D+&bg=ffffff&fg=777777&s=0&c=20201002) (7)

(7)

We see from this that we have simplified assembling the constitutive matrix considerably. From a coding standpoint, doing this eliminates not only the possibility of coding error but also computational cost by eliminating the sheer number of operations. This is especially useful if these matrices are reconstituted during the analysis (as one would expect if strain-softening is applied, for example.)

If we multiply the left hand side through, we have

![\left[\begin{array}{c} \sigma_{{x}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\sigma_{{y}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\sigma_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it xy}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it yz}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\tau_{{\it zx}} \end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{c} {\frac{\left(1-\nu\right)\lambda\,\epsilon_{{x}}}{\nu}}+\lambda\,\epsilon_{{y}}+\lambda\,\epsilon_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\lambda\,\epsilon_{{x}}+{\frac{\left(1-\nu\right)\lambda\,\epsilon_{{y}}}{\nu}}+\lambda\,\epsilon_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\lambda\,\epsilon_{{x}}+\lambda\,\epsilon_{{y}}+{\frac{\left(1-\nu\right)\lambda\,\epsilon_{{z}}}{\nu}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}G{\it \gamma}_{{\it xy}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}G{\it \gamma}_{{\it yz}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}G{\it \gamma}_{{\it zx}} \end{array}\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+%5Csigma_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7By%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D+%3D+%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Cnu%7D%7D%2B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7By%7D%7D%2B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%2B%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7By%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Cnu%7D%7D%2B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%2B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7By%7D%7D%2B%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cleft%281-%5Cnu%5Cright%29%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Cnu%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7DG%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7DG%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7DG%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D+&bg=ffffff&fg=777777&s=0&c=20201002) (8)

(8)

Inversely, if we want to know the strains, we would compute these by the relationship

(9)

(9)

Inverting,

![D_{e}^{-1}=\left[\begin{array}{cccccc} -{\frac{\nu}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & {\frac{{\nu}^{2}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & {\frac{{\nu}^{2}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{{\nu}^{2}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & -{\frac{\nu}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & {\frac{{\nu}^{2}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{{\nu}^{2}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & {\frac{{\nu}^{2}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & -{\frac{\nu}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}} & 0 & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & {G}^{-1} & 0 & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & {G}^{-1} & 0\\ \noalign{\medskip}0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & {G}^{-1} \end{array}\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=D_%7Be%7D%5E%7B-1%7D%3D%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bcccccc%7D+-%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+-%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+-%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cnu%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+%7BG%7D%5E%7B-1%7D+%26+0+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+%7BG%7D%5E%7B-1%7D+%26+0%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+0+%26+%7BG%7D%5E%7B-1%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D+&bg=ffffff&fg=777777&s=0&c=20201002) (10)

(10)

and the strains can be computed as follows

![\left[\begin{array}{c} \epsilon_{{x}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\epsilon_{{y}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\epsilon_{{z}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}\gamma{}_{{\it xy}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\it \gamma}_{{\it yz}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\it \gamma}_{{\it zx}} \end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{c} -{\frac{\nu\,\sigma_{{x}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}+{\frac{{\nu}^{2}\sigma_{{y}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}+{\frac{{\nu}^{2}\sigma_{{z}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{{\nu}^{2}\sigma_{{x}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}-{\frac{\nu\,\sigma_{{y}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}+{\frac{{\nu}^{2}\sigma_{{z}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{{\nu}^{2}\sigma_{{x}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}+{\frac{{\nu}^{2}\sigma_{{y}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}-{\frac{\nu\,\sigma_{{z}}}{\lambda\,\left(-1+\nu+2\,{\nu}^{2}\right)}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{\tau_{{\it xy}}}{G}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{\tau_{{\it yz}}}{G}}\\ \noalign{\medskip}{\frac{\tau_{{\it zx}}}{G}} \end{array}\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cepsilon_%7B%7By%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cepsilon_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%5Cgamma%7B%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cit+%5Cgamma%7D_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D+%3D+%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+-%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cnu%5C%2C%5Csigma_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D%2B%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7By%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D%2B%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D-%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cnu%5C%2C%5Csigma_%7B%7By%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D%2B%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7Bx%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D%2B%7B%5Cfrac%7B%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Csigma_%7B%7By%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D-%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Cnu%5C%2C%5Csigma_%7B%7Bz%7D%7D%7D%7B%5Clambda%5C%2C%5Cleft%28-1%2B%5Cnu%2B2%5C%2C%7B%5Cnu%7D%5E%7B2%7D%5Cright%29%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+xy%7D%7D%7D%7BG%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+yz%7D%7D%7D%7BG%7D%7D%5C%5C+%5Cnoalign%7B%5Cmedskip%7D%7B%5Cfrac%7B%5Ctau_%7B%7B%5Cit+zx%7D%7D%7D%7BG%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D++&bg=ffffff&fg=777777&s=0&c=20201002) (11)

(11)

Relationships such as Equations (8) and (11) will be more useful when we consider two-dimensional problems.

References

- Cook, R.D., Malkus, D.S. and Plesha, M.E. (1989). Concepts and Applications of Finite Element Analysis, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY

- Owen, D.R.J., and Hinton, E. (1980). Finite Elements in Plasticity: Theory and Practice. Pineridge Press, Swansea, Wales.

- Smith, I.M., and Griffiths, D.V. (1988). Programming the Finite Element Method. Second Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, England.

Note: after this was first posted, some errors were discovered. These were corrected with the assistance of Jaeger, J.C. and Cook, N.G.W. (1979) Fundamentals of Rock Mechanics. London: Chapman and Hall. This book has an excellent treatment of basic theoretical solid mechanics in general and elasticity in particular. Although they do not put the equations in matrix form, they do use the Lamé constants in their formulation, albeit in a different way than is done here. We apologise for any inconvenience or confusion.

(1a)

(1b)

(1c)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

(7)

(8)

(9)

:

(10)

would look thus:

(11)

is

(12)

(13)

(14)

.

(15)

(16)

.