My students in Soil Mechanics and Foundations get introduced to some strange concepts. One of those is what I call the “old coot” method of statics, which I discuss here. Related to that is the concept of the “resultant.” Introduction of these concepts leads to puzzlement, which students generally hide in class, as many engineering students would make great professional poker players. But homework and tests do not lie…

Most all loads in geotechnical engineering are distributed loads, because they are the results of earth pressures, either horizontal (lateral) or vertical. Although most of these are either constant or ramped linear, the math with these gets complicated fast. In the past this was a major problem for geotechnical engineers armed with slide rules. The resultant is one way of simplifying the computations, and at the same time it offers better understanding of how earth pressures either load a structure or support it.

Let’s start with a definition: for most geotechnical problems, a resultant is a point load which is used to represent a distributed load. In general statics, the definition is broader, but this is what we’re going to discuss here. To accomplish this such a resultant must meet two criteria:

- It must have the same total load as the distributed load.

- It most pass through the centroid of the distributed load.

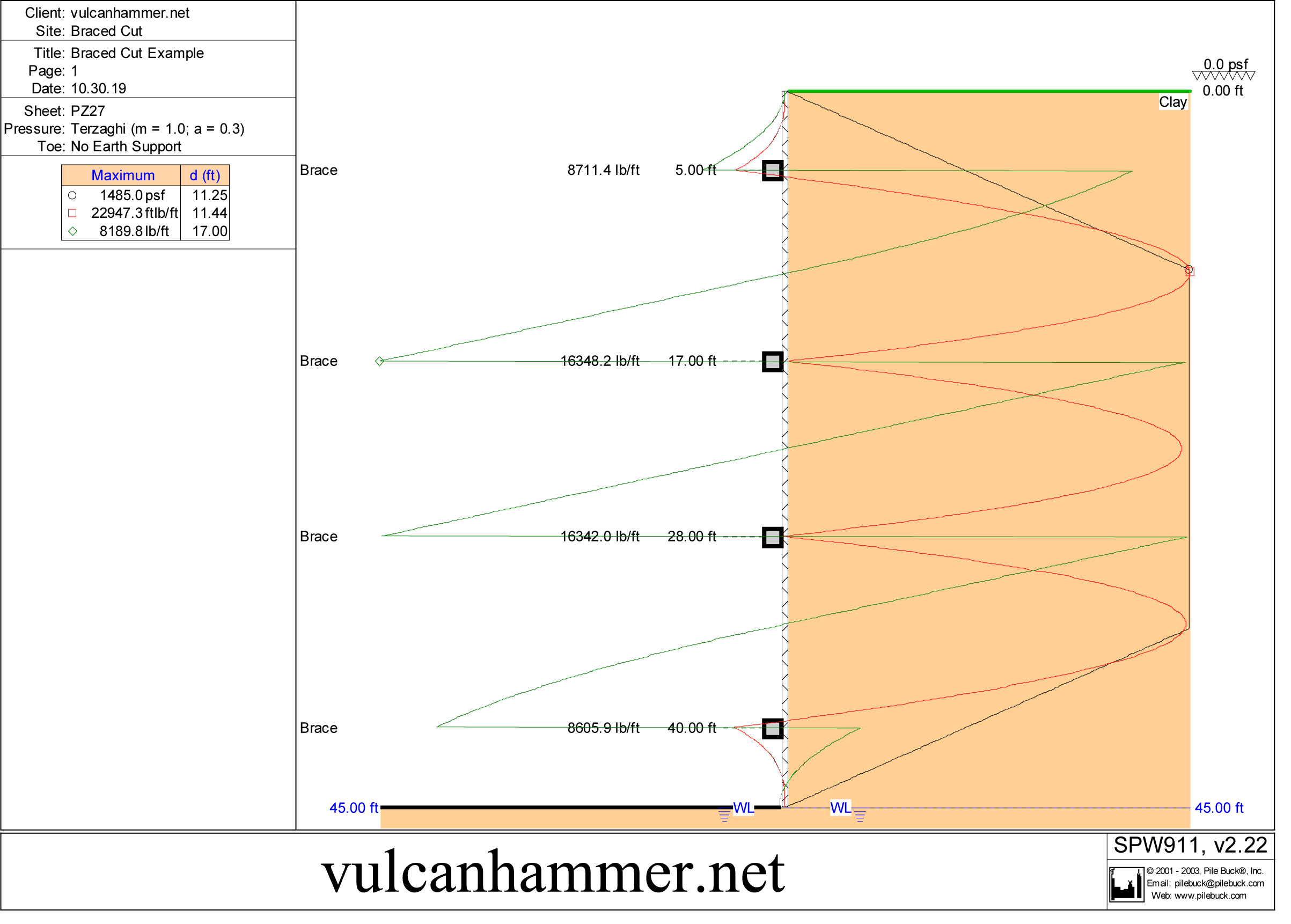

The example we’ll use here is from a previous post on braced cut analysis, a subject that has buffaloed many of my students over the years. The software layout of the wall, earth pressure loads, shears and moments is shown below.

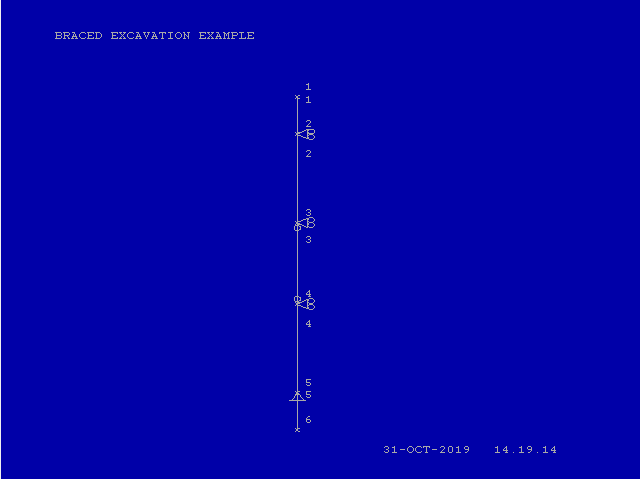

Using CFRAME to focus on the beam mechanics of the problem, first we will look at the model itself.

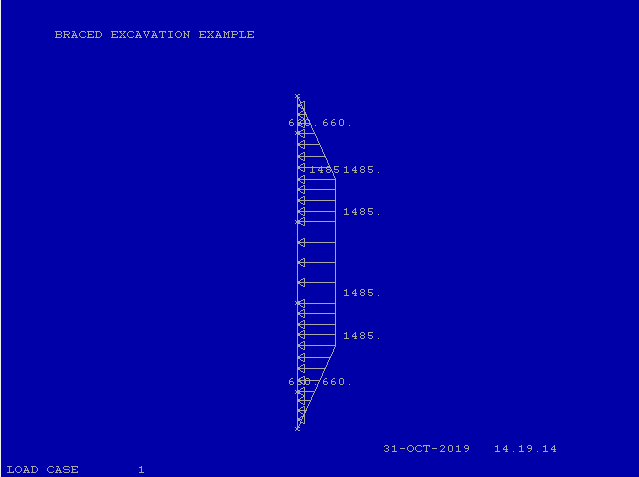

The distributed loading is then shown below.

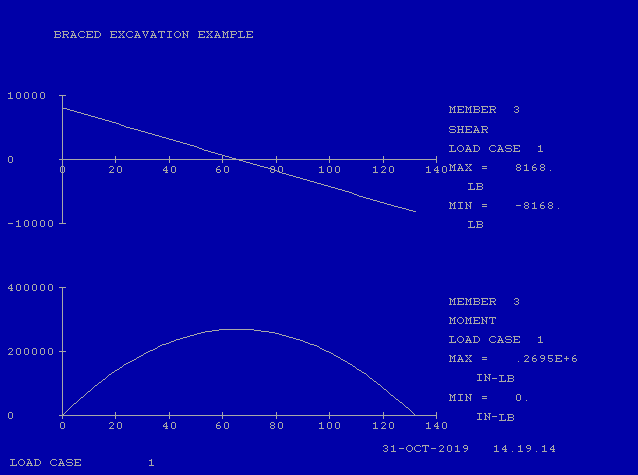

Let’s start with the easy section: the portion of the wall between 17′ and 28′ below the top of the wall (Element 3, between Nodes 3 and 4, shown in the basic layout.) As noted above, the beam has a distributed uniform of 1485 psf, or for our purposes 1485 lb/ft/ft of wall (vertical) and is simply supported on both ends. With this load the shear and moment looks like this, taken from the CFRAME program:

The way Terzaghi and Peck set this method forth, the beams at the top and bottom of the wall would be considered to be cantilever beams and the rest simply supported beams. This turns the whole problem into a statically determinate one, necessary to simplify the calculations. The diagram above shows a reaction of 8168 lbs. at each end, a maximum moment of 269,500 in-lb at the centre, and zero moment at the supports (due to the simply supported assumption.)

We could obtain this result by hand calculations. First, the reactions at the supports are given by the formula

(1)

which is the same as above. The maximum moment is given by the equation

(2)

which is also the same as above.

Note: one of my students got very put out with me because I had the bad taste to say that these formulas were in the "steel book," the AISC Steel Construction Manual. While I realise that it's hard to find anything in the steel book, they are there, and have been since the days I first used it at the Special Products Division.

Now let’s replace the distributed load by a resultant point load. Since the load is uniformly distributed, the centroid is at the centre of the beam. The resultant is

(3)

The reactions are computed by symmetry as follows:

(4)

and the maximum moment (at the centre of the beam) is

(5)

The reactions at the braces are the same. Thus, for the design of the braces, the methods give the same result. The maximum moment from the resultant, however, is twice the moment from a point load resultant. In practice one could deal with this problem by a) assuming the uncertainty in the earth loads justifies the conservatism of the resultant, b) scaling down the anticipated moment by noting the differences between the two (which are in turn the result of the statics of simply supported beams) or c) a combination of the two. In any case the need to use a resultant here isn’t great because of the uniform load.

Things get more complicated when we consider the second segment from the top, from 5′ to 17′. This 12′ long segment has the following pressure distribution:

- At the top end of the beam, the pressure is 660 psf.

- The pressure ramps up linearly to the maximum pressure of 1485 psf at a point 6.25′ from the end of the beam.

- From this point until the bottom end of the beam 12′ from the top the pressure is uniform at 1485 psf.

Although it’s possible to get resultants from ramped load, it’s easier to divide a ramped load into a constant portion (minimum pressure) and a triangle load from zero to the difference between the minimum and maximum pressures. That being the case, the three regions are as follows, with their resultants:

- The upper uniform region has a pressure of 660 psf and a length of 6.25′, thus its resultant is (660)(6.25) = 4125 lb/ft

- The triangular region has a maximum pressure of 1485-660=825 psf, thus its resultant is (825)(6.25)/2 = 2578 lb/ft. The division by 2 is because it’s a triangle load.

- The lower uniform region has a pressure of 1485 psf and a length of 12-6.25 = 5.75′, thus its resultant is (1485)(5.75) = 8539 lb/ft.

The location of these resultants is as follows:

- The upper uniform region is half the length of the region, thus it is 6.25/2 = 3.125′ from the top end.

- The upper triangular region is two-thirds the length of the region, thus it is 2*6.25/3 = 4.17′ from the top end

- The lower uniform is the length of the upper region plus half the length of the lower region, thus it is 6.25 + 5.75/2 = 9.125′.

The reactions for a point load at any point in the beam are given by the equation

(6)

(7)

The variable k is the ratio of the distance from the top end of the resultant to the total beam length. We can add the contribution from each resultant to obtain total reactions.

| Resultant | Fres, lb/ft | Location from top, ft | k | R1 | R2 |

| 1 | 4125 | 3.125 | 0.26 | 3053 | 1073 |

| 2 | 2578 | 4.17 | 0.35 | 1676 | 902 |

| 3 | 8539 | 9.125 | 0.76 | 2046 | 6493 |

| Total | 15,242 | 6775 | 8468 |

It can be shown that the sum of the reactions is the same as the sum of the resultants within rounding error, as should be the case.

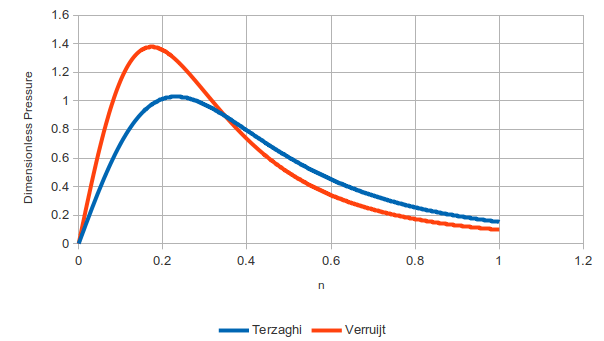

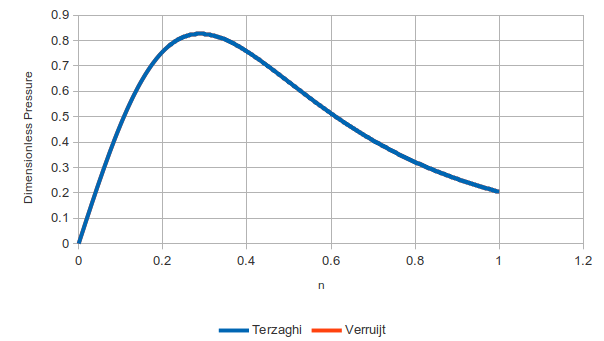

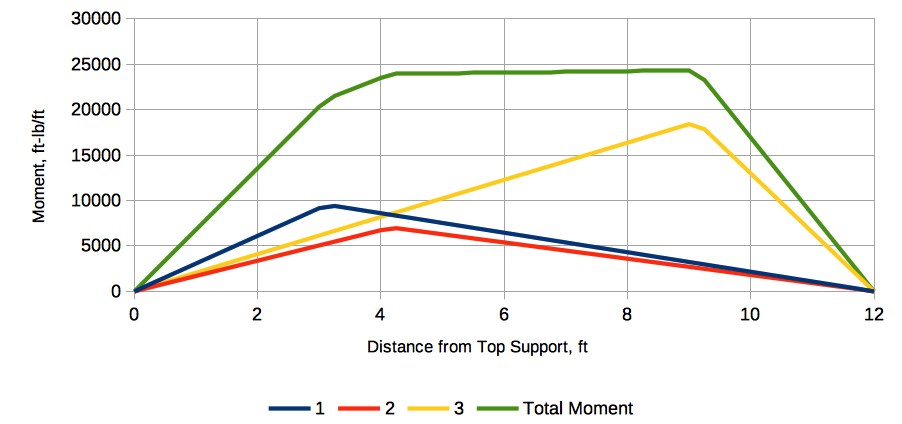

The maximum moment is a little more complicated. For any point load on a simply supported beam, the moment begins at zero at the support, linearly rises to a maximum of , and then linearly declines to zero at the opposite support. This means that each moment distribution needs to be determined at many points and then the result summed at each point to insure that the maximum moment is identified. The spreadsheet implementation of this is here and you can see the moment distribution for each resultant and their sums below. The maximum moment is 24,322 ft-lbs/ft = 291,869 in-lbs/ft.

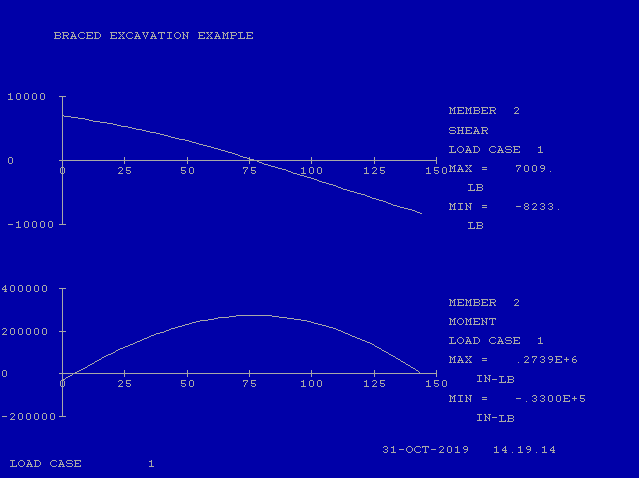

Now let’s compare this with the CFRAME results, which took into consideration distributed loads. Hand calculations for distributed loads are fairly involved.

We’ll start with the moment. The maximum moment from CFRAME (273,900 in-lb/ft) is a little smaller that that which is predicted by the resultants. This is expected; the more resultants the load is divided into, the closer to the distributed load result the moment will become.

With the reactions, the sum of the reactions shown in CFRAME is identical to those from the resultant method; however, the reactions themselves are different. That’s because it is not possible to accurately reproduce a simply supported beam for Segment 2 and have a cantilever beam for Segment 1. In CFRAME we are forced to use a continuous beam from the top to the second brace (17′) and simply support them at both points. Note carefully that the moment at the left (top) end of the beam is nonzero, which is not the case with a simply supported beam. This illustrates that, from a structural standpoint, the method of Terzaghi and Peck for braced cuts is artificial, although it is possible to combine Segments 1 and 2 and do hand calculations for these with resultants.

It’s worth noting that the brace loads using SPW911 at 17′ and 28′ are 16,340 lb/ft of wall. If we use the resultant method, the brace loads (the structure is symmetric) should be 8468 + 8168 = 16,636 lb/ft and using CFRAME 8233 + 8168 = 16,401, neither of which are identical to SPW 911. This is a good illustration of the care you need to take when evaluating computer generated results.

Nevertheless, I think the use of resultants is adequately illustrated by this example. Perhaps in the future more examples of resultants can be given.