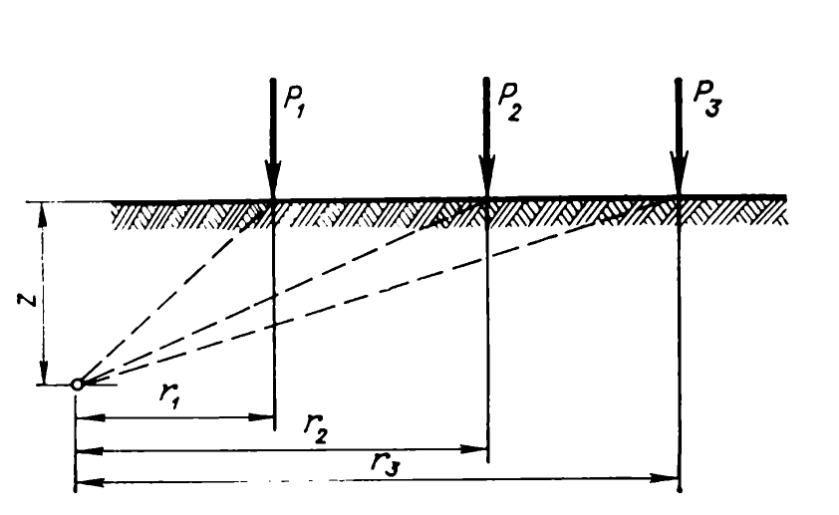

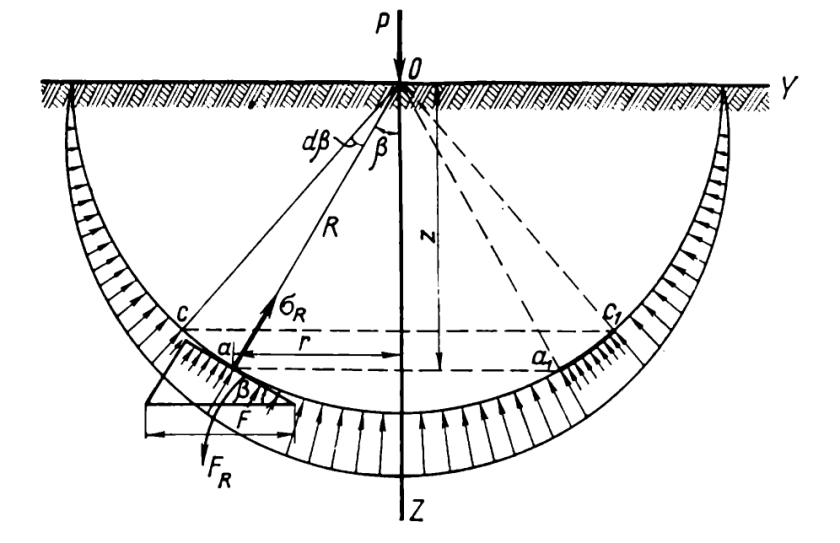

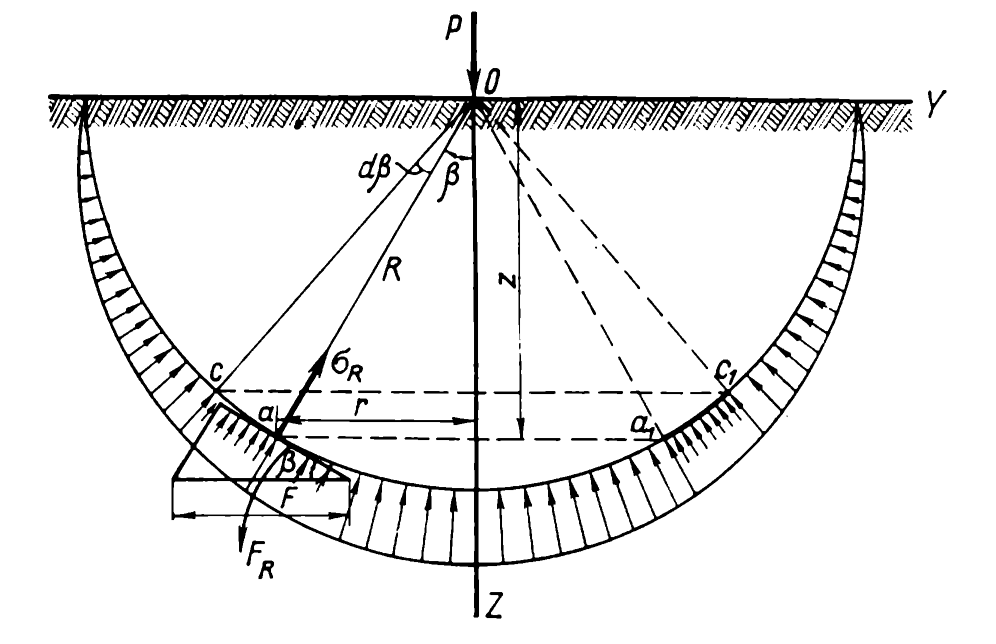

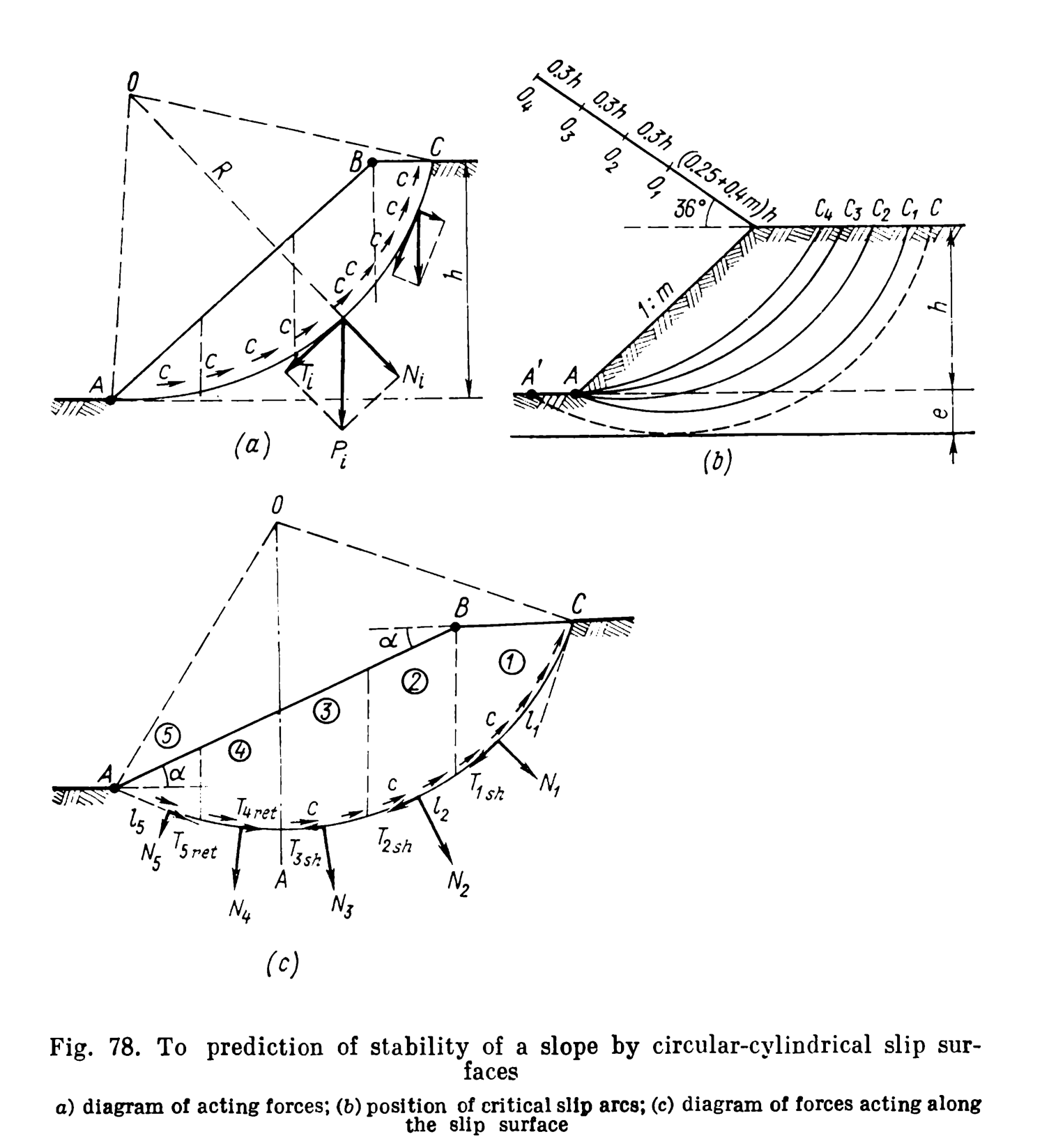

Slope stability for circular failure surfaces is one of those topics where, for a complete solution, solving the problem has involved a computer solution before there were computers. The problem is that it is necessary to a) discretise the problem before solving it, in this case using slices, and b) try a large number of circle centre locations before finding the right one. The problem is illustrated below.

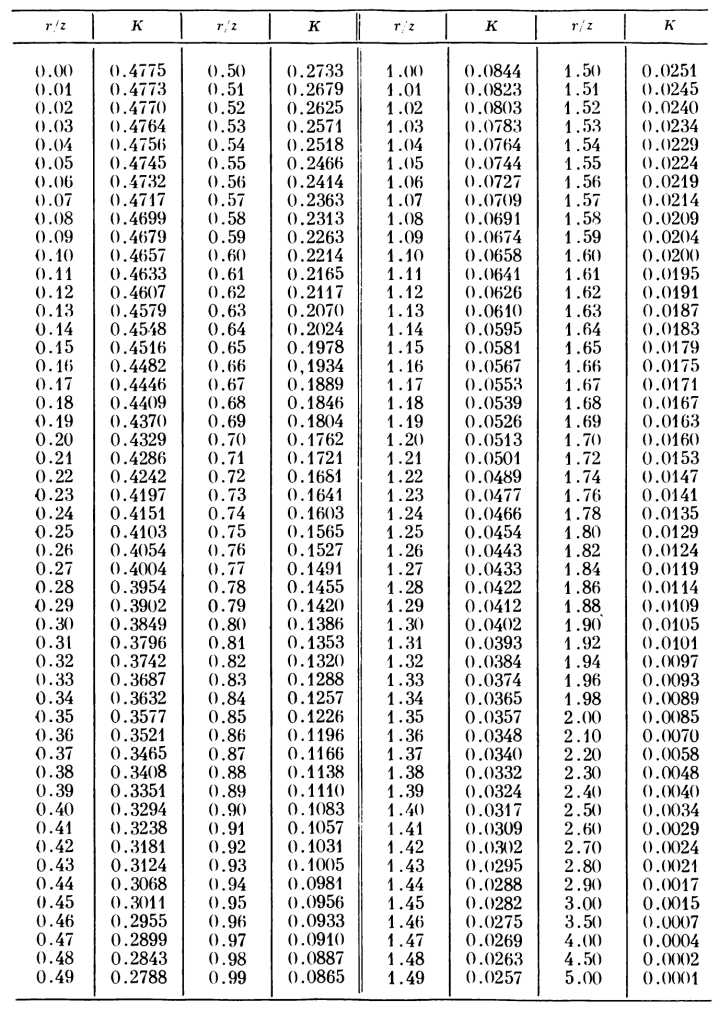

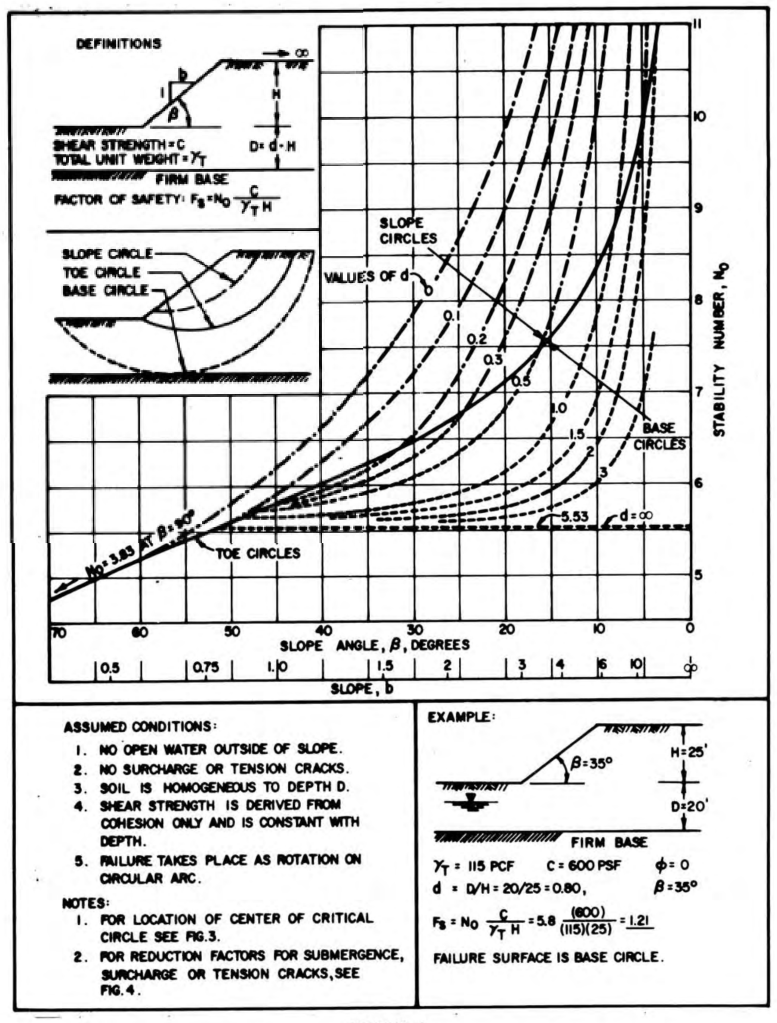

One common method has been to use charts. A commonly used group is the Janbu series of charts, one of which is shown below.

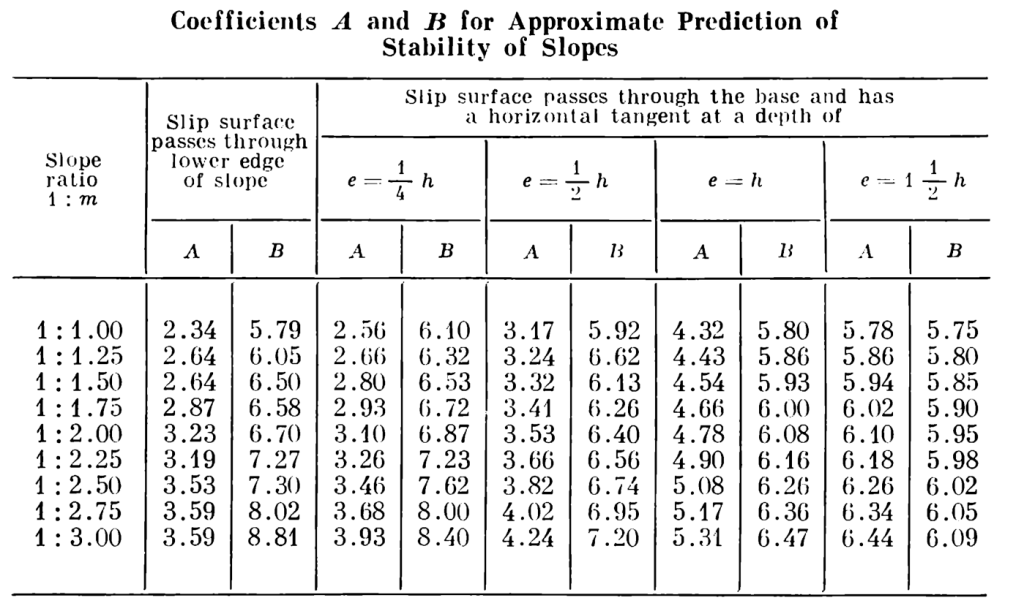

A simpler solution is presented by Tsytovich (1976). The equation proposed there is this:

(1)

where

factor of safety

internal frictional angle of the soil

cohesion of the soil

unit weight of the soil

coefficients given below, functions of

and

= distance from slope toe to hard underground layer (see Figure 78(b))

= height of slope from toe to top (see Figure 78(b))

= second number of slope ratio rise:run (see Figure 78(b))

It is also possible to solve for a maximum height, thus:

(2)

As an example, consider a slope with an angle of 35 degrees and a height of 20′. The soil has an internal friction angle of 15 degrees, a cohesion of 600 psf and a unit weight of 120 pcf. Estimate the factor of safety against slope failure using the method described. For this slope e = 0, so assume the slip surface passes through the lower edge (toe) of the slope.

The slope ratio 1:m is the reciprocal of the tangent of the slope given. Taking the tangent and inverting it gives a slope ratio of 1:1.43. It can be seen by inspection that A = 2.64 and through interpolation B = 6.38. Direct substitution yields a factor of safety of 2.3.

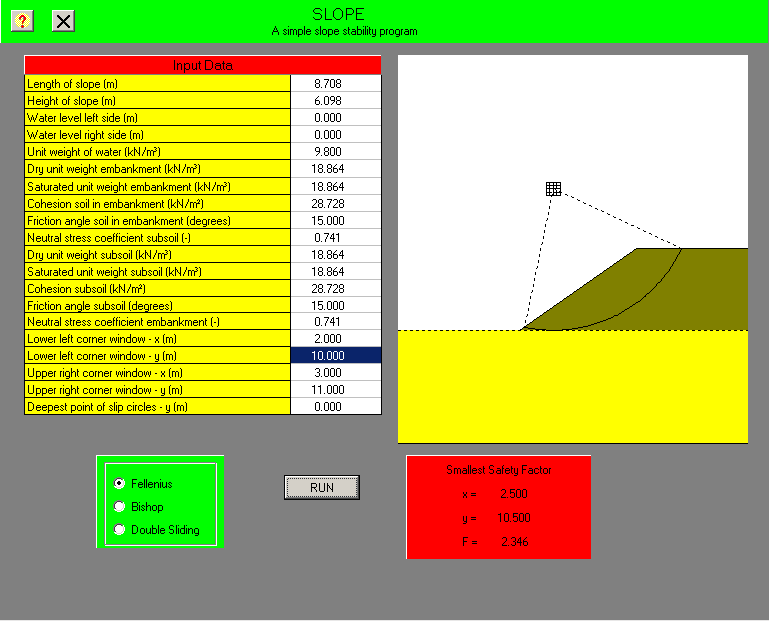

As a comparison we use the Slope program from our Soil Mechanics Course, the results are shown below using Fellenius’ Method.

The factor of safety is very close. If we used Bishop’s Method in the program, we could expect the factor of safety to increase. One thing absent from this problem is the presence of water, which always complicates slope stability analysis.

If we consider the example problem from the Janbu chart above, Equation (1) reduces to the equation for FS on the chart provided that . Doing the linear interpolation yields

, which is higher than the

on the chart, or

.

Obviously the method is not suitable for final design but it is interesting for producing preliminary results for a problem which has traditionally been computationally difficult.