For retaining walls, computing these is important; but the textbooks and reference books are frequently confusing and sometimes wrong. These formulae, derived using Maple, should clear up a few things, although they’re a) not always in the format you’re used to and b) subject to the Terms and Conditions of this site.

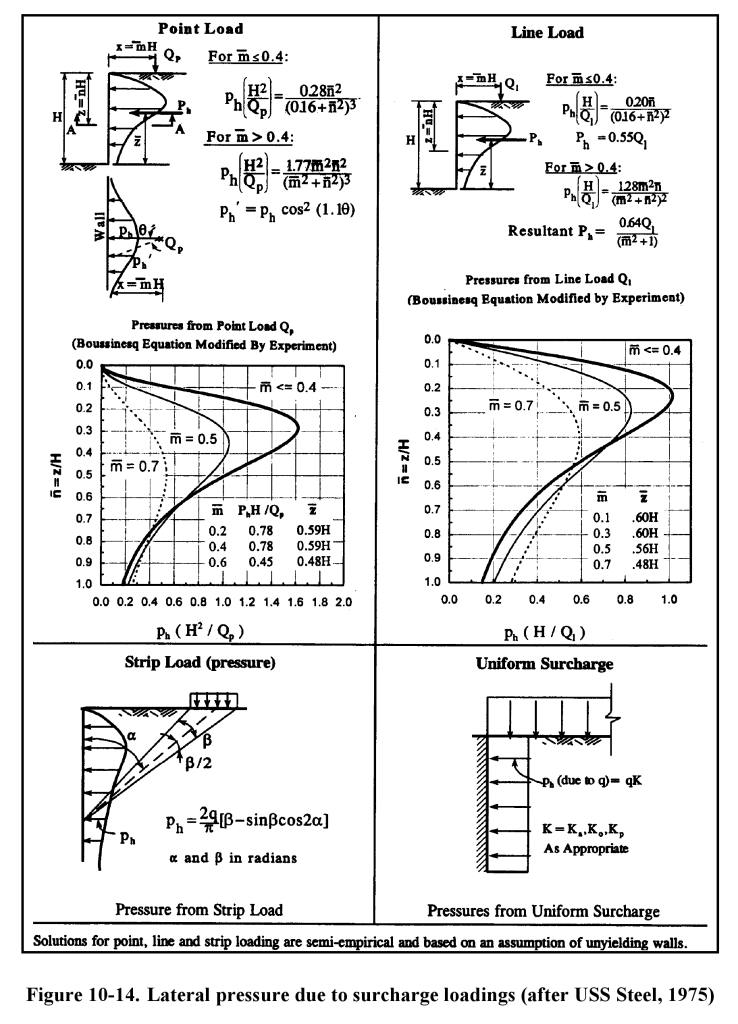

Let’s start with a diagram and the basic Coulomb formulae, from NAVFAC DM 7.02, shown above. It’s important for to have a nomenclature chart for any lateral earth pressure coefficient formulae.

Coulomb Active Coefficients

All angles nonzero:

(1a)

Vertical Wall:

(1b)

Level Backfill:

(1c)

Vertical Wall and Level Backfill:

(1d)

Coulomb Passive Coefficients

All angles nonzero:

(1e)

Vertical Wall:

(1f)

Level Backfill:

(1g)

Vertical Wall and Level Backfill:

(1h)

Rankine Active Coefficients

These were derived assuming that Rankine coefficients are the same as their Coulomb counterparts except for ). This is strictly speaking not the case and will be discussed in detail below.

Sloping Wall and Backfill:

(2a)

Vertical Wall:

(2b)

Level Backfill:

(2c)

Vertical Wall and Level Backfill:

(2d)

Rankine Passive Coefficients

These were derived assuming that Rankine coefficients are the same as their Coulomb counterparts except for ). This is strictly speaking not the case and will be discussed in detail below.

(2e)

Vertical Wall:

(2f)

Level Backfill:

(2g)

Vertical Wall and Level Backfill:

(2h)

The Origin of Rankine Earth Pressure Coefficients

It is a matter of record that Rankine earth pressure coefficients were derived from a combination of Mohr-Coulomb failure theory and the effect of wall movement on the horizontal earth pressure. The physical manifestation of the theory is illustrated at the right, based on tests which have been run over the years.

OTOH, Coulomb earth pressures were derived from the static equilibrium of a soil wedge (with a failure surface, see diagram at left.)

The thing that has confused the issue is that, for the case of level backfill, vertical wall and no wall friction, the results of Equations (2d) and (2h) are identical with the Rankine theory results as originally derived. This equivalence is doubtless more than fortuitous but it does not necessarily extend upwards to the other cases.

This has been recognised for a long time. For the case of the vertical wall and sloping backfill, the application of “conjugate stresses” (Hough, 1970) as opposed to principal stresses results in the following “Rankine” earth pressure coefficient:

(3)

and its passive counterpart

(4)

Ebeling and Morrison (1992) note the following about Equation (3):

The Rankine active earth pressure coefficient for a dry frictional backfill inclined at an angle

from horizontal is determined by computing the resultant forces acting on vertical planes within an infinite slope verging on instability, as described by Terzaghi (1943) and Taylor (1948).

Equations (2b) and (3) reduce to Equation (2d) and Equations (2f) and (4) reduce to Equation (2h) when .

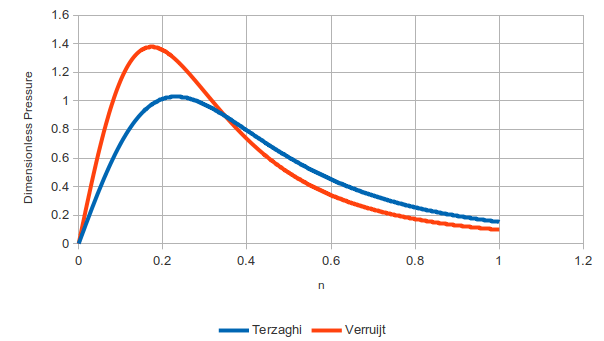

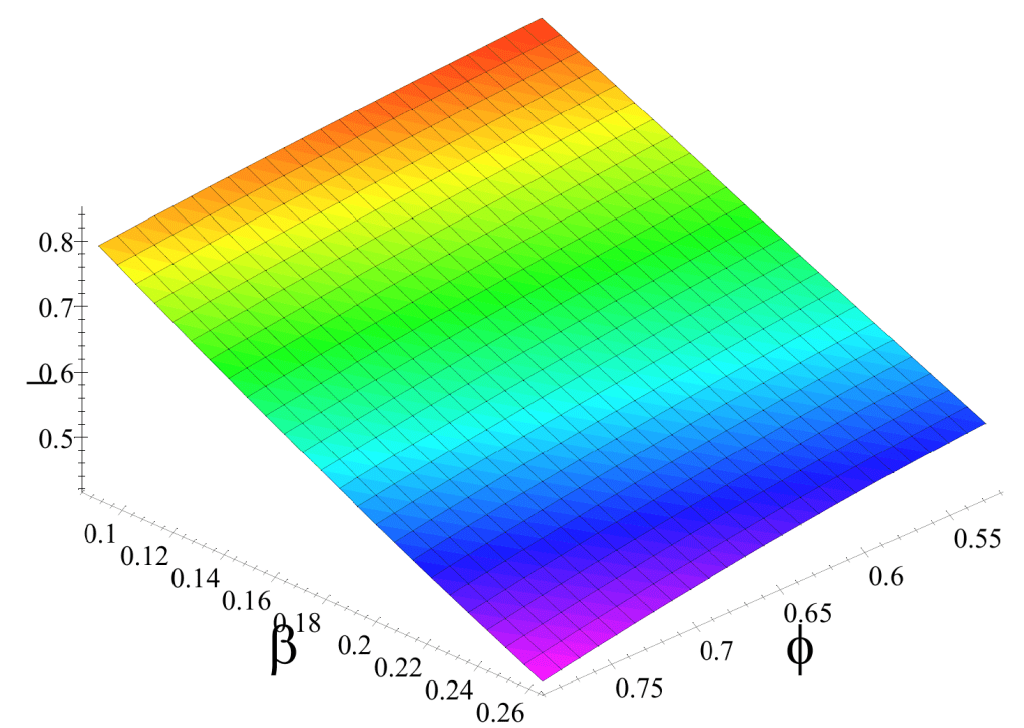

A quick comparison was made by dividing the right hand side of Equation (3, numerator) by the right hand side of Equation (2b, denominator.) A survey of the results are shown below. The angles are shown on the x- and y-axes in radians; the friction angle varies from 30 to 45 degrees and the backfill angle

varies from 5 to 15 degrees. The result shows that the Terzaghi and Taylor (an interesting combination to say the least) coefficients are slightly lower than the Coulomb derived coefficients.

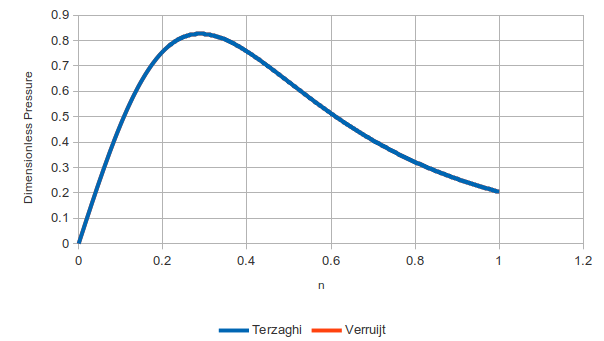

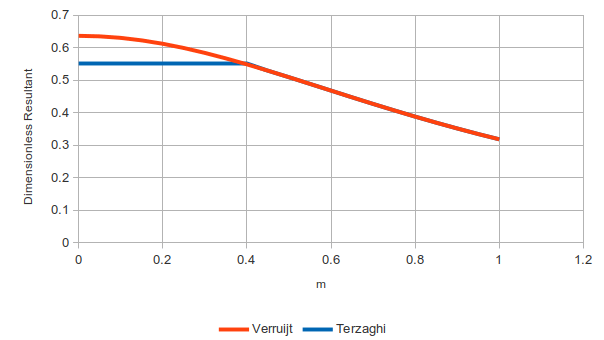

It’s a completely different story with the passive coefficients; dividing the right hand side of Equation (4) by the right hand side of Equation (2f) with the same angle ranges as above gives us the following result:

As an interesting side note, if we take a test case of φ = 30 deg. and β = 10 deg., the passive coefficient using Equation (4) is actually less than the one for level backfill!

This is a topic that deserves further investigation; however, extending Rankine theory using Coulomb wedge theory without wall friction has merit for those applications (such as vinyl or fibreglass sheet piling) where inclusion of wall friction is inappropriate to the application.

References

Hough, B.K. (1970) Basic Soils Engineering. Second Edition. New York: The Ronald Press Company.