On this site we feature the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers publication Retaining and Flood Walls, which details the design of several types of retaining walls. As it was published a good while back, it details the design of these walls using hand calculations. Sometimes these can get tedious, especially when the aptly named “trial wedge” solutions are employed.

These days it’s more likely that a computer solution–be it a true finite element analysis or simply the automation of those tedious hand calculations–is used to finalise the design of a retaining wall. An example of such an analysis is shown above, and addresses in particular an issue that gets the short shrift in classical retaining wall analysis of any kind: global stability failure. An idea of a hand solution to this problem is shown at the right. Global stability failures still happen and are generally disastrous; beyond a conventional slope their analysis is fairly complex.

But in the meanwhile, what do we do to verify that we’ve got it right with a computer solution? Or what can we do to start with a reasonable design that we can refine with numerical analysis? Back in the “slide rule era” we used quick, “back of the envelope” methods to design things, and we can use them today both to get started and to gain a basic understanding of the elements of the design.

In this case we’re going to discuss the design of a cantilever retaining wall, an example of which is shown below.

The methodology is based on the aforementioned Retaining and Flood Walls and the example (which is a little clearer description of same) comes from Appendix A of Seismic Analysis of Cantilever Retaining Walls, Phase I. I’ve modified it in a couple of spots and will detail those modifications as we go.

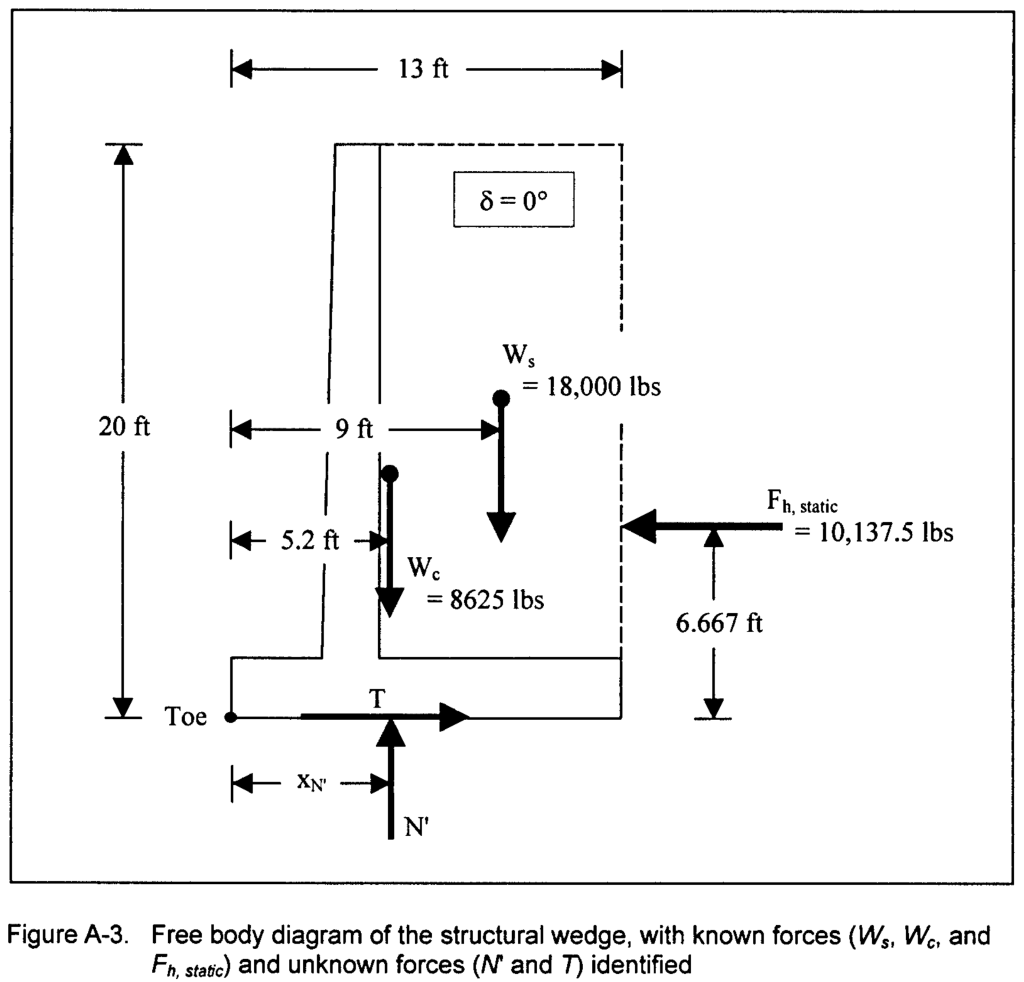

The example we’ll look at is below. We need to design this wall to prevent failure against three events: sliding, overturning and bearing capacity failure.

Defining the Geometry, Weights and Centres of Gravity

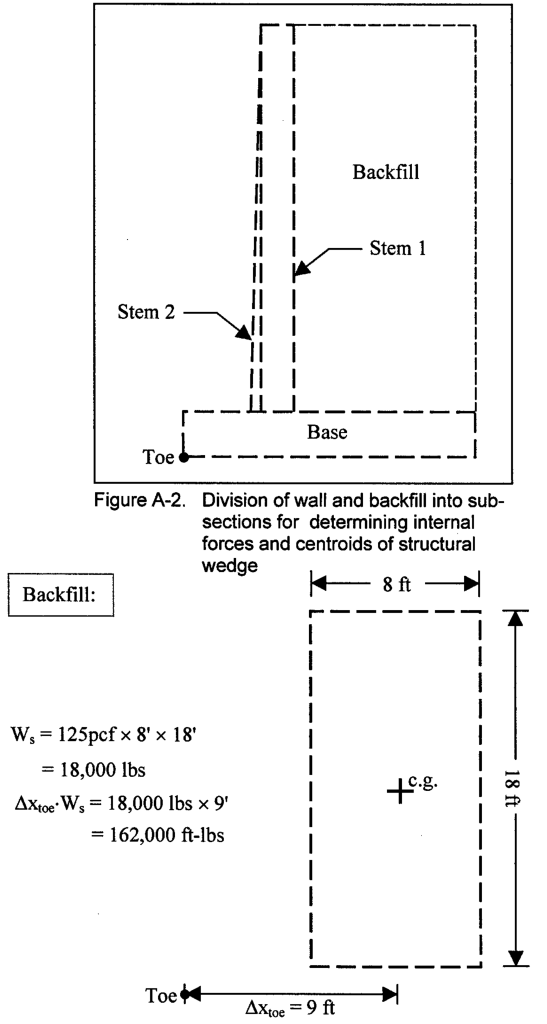

Our datum/coordinate origin is at the toe, which is convenient since we assume that the overturning moment is computed around the toe. Since this is a cantilever/gravity wall, the weight of the wall is part of the resistance force and moment. Included with that is the backfill that is trapped behind the wall (shown above.)

We start by dividing up the wall into sections, each of which has a weight and a centre of gravity. The first section we take up is the backfill, which is a simple rectangle shown above.

At this point we need to make one correction to the Corps’ work: the weights and moments are in pounds per unit length of wall and ft-pounds per unit length of wall, respectively. Leaving those per unit length designations is a common shortcut among practitioners but is confusing for students, who frequently find the unit length concept difficult to grasp at first. The weight of the backfill is properly 18,000 lbs/ft of wall and the moment around the toe ((clockwise) is 162,000 ft-lbs/ft of wall.

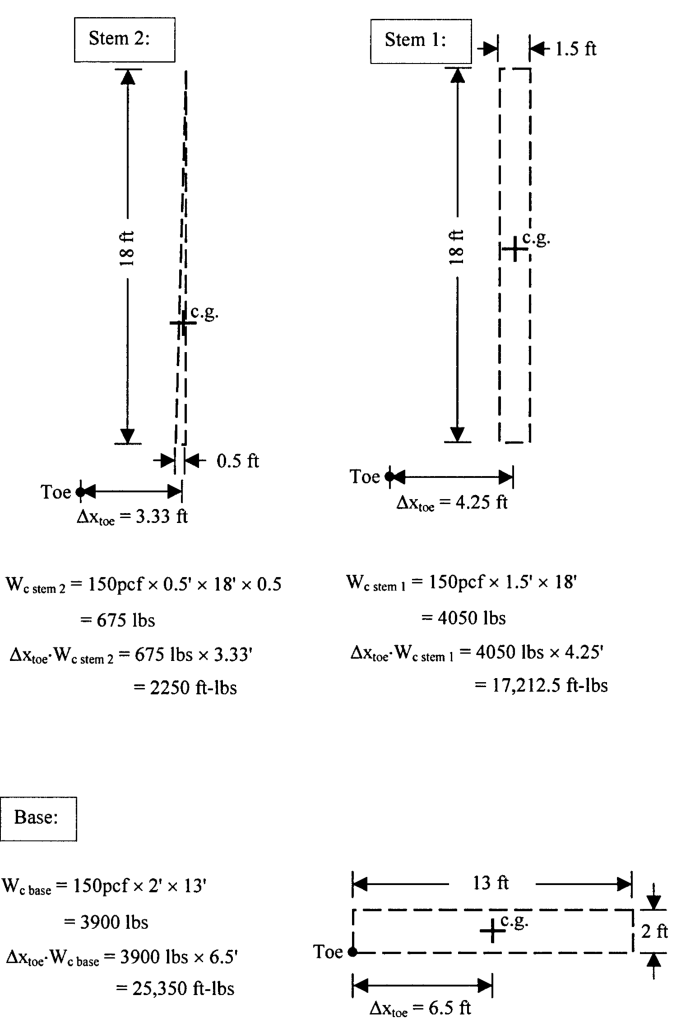

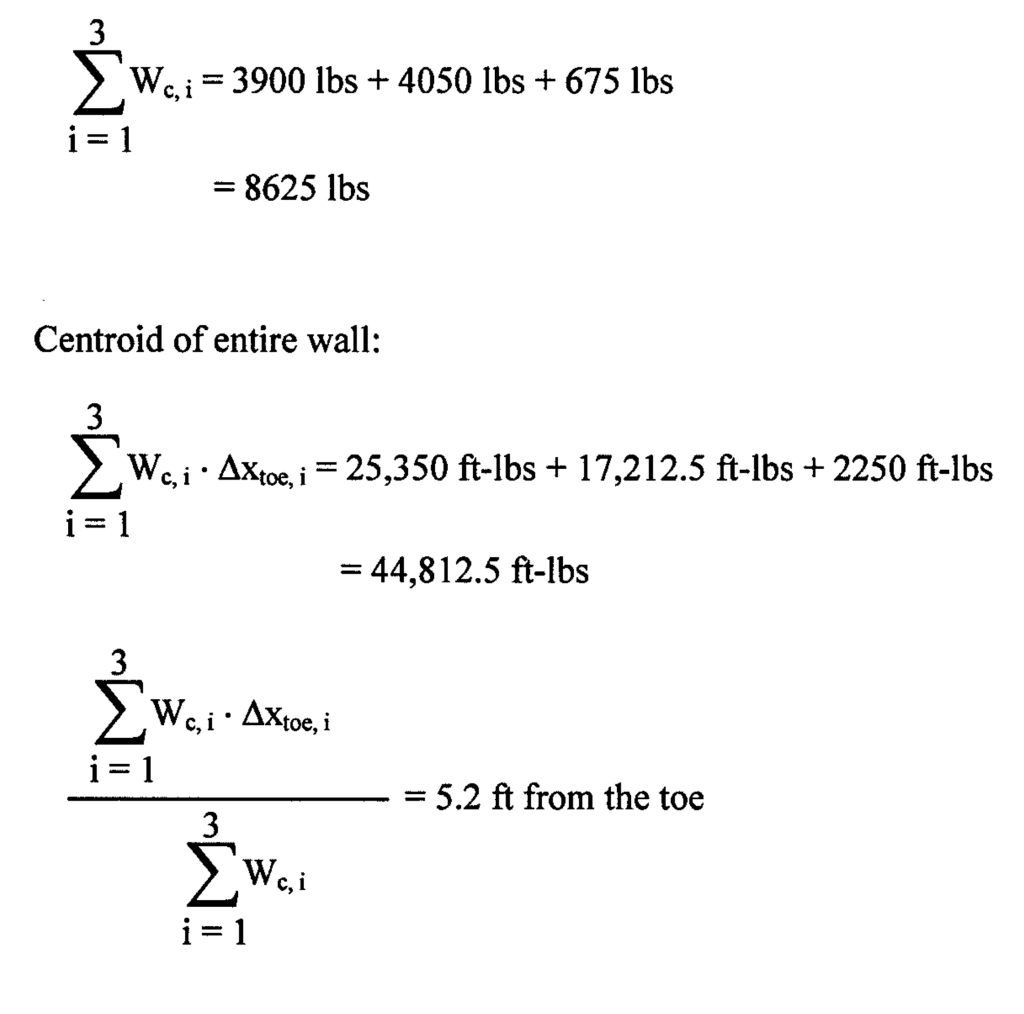

Computing the weights and moments of the various sections of the wall itself yields the following results.

Taking all of this information and processing it yields the total weight, total moment around the toe, and moment arm around the toe:

Since most engineers have learned their statics via vectors, a review of Vector Statics and “Old Coot” Statics: An Example and What is a Resultant in Geotechnical Engineering? may be in order.

The Shear Mobilisation Factor

Now comes the tricky part: in retaining wall design, we traditionally define the factor of safety as

(1)

Where the “F” values can be forces or moments and FS is the factor of safety. Sometimes this is not the optimal way of applying factors to account for uncertainties, especially when we get to LRFD. Another approach is either to increase the driving force or reduce the resisting force. We do the latter with sheet piling (where there there are earth forces to resist) but here we’ll to the former. To make this happen we first define a shear mobilisation factor (SMF) thus

(2)

The value of can be computed thus:

(3)

For this problem, assuming SMF = 2/3 and φ’ = 35°, by substitution φ’mob = 25°. We will discuss the effect of cohesion later.

Now we turn to computing the force of the soil behind the wall on the wall.

We note the following:

- Rankine theory is used. Methods shown in both Retaining and Flood Walls and the Soils and Foundations Reference Manual use Coulomb and/or log-spiral for these computations. The problem with this is that the value of wall friction δ is sometimes difficult to determine without data or experience, and in reality most of this pressure bears on soil, not the wall. So Rankine is easier to start with, and is more conservative.

- The backfill is level, the formula for Ka only applies in that case. We will discuss sloping backfill below.

- Note that φ’mob (not φ’ ) is being used to compute the soil force.

Analysing Sliding and the Location of the Resultant/Overturning

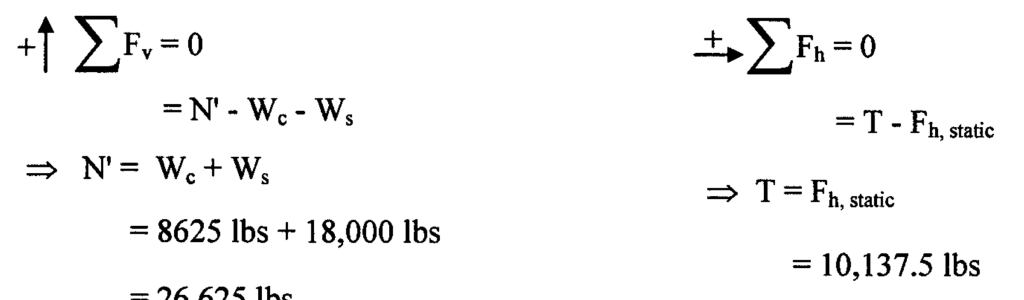

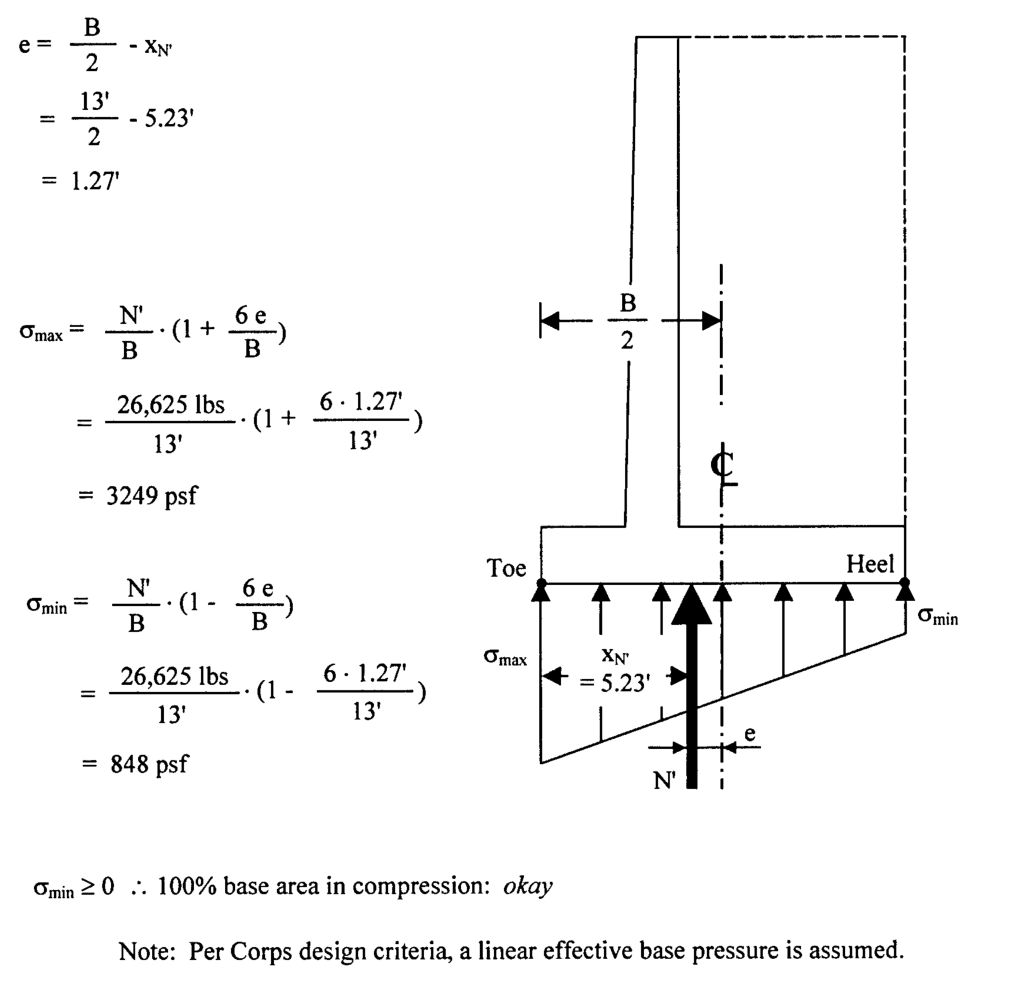

At this point we can compute the forces on the base (both the forces T’ and N’ and the location of the resultant xN’,) which are shown below.

The calculations are shown below.

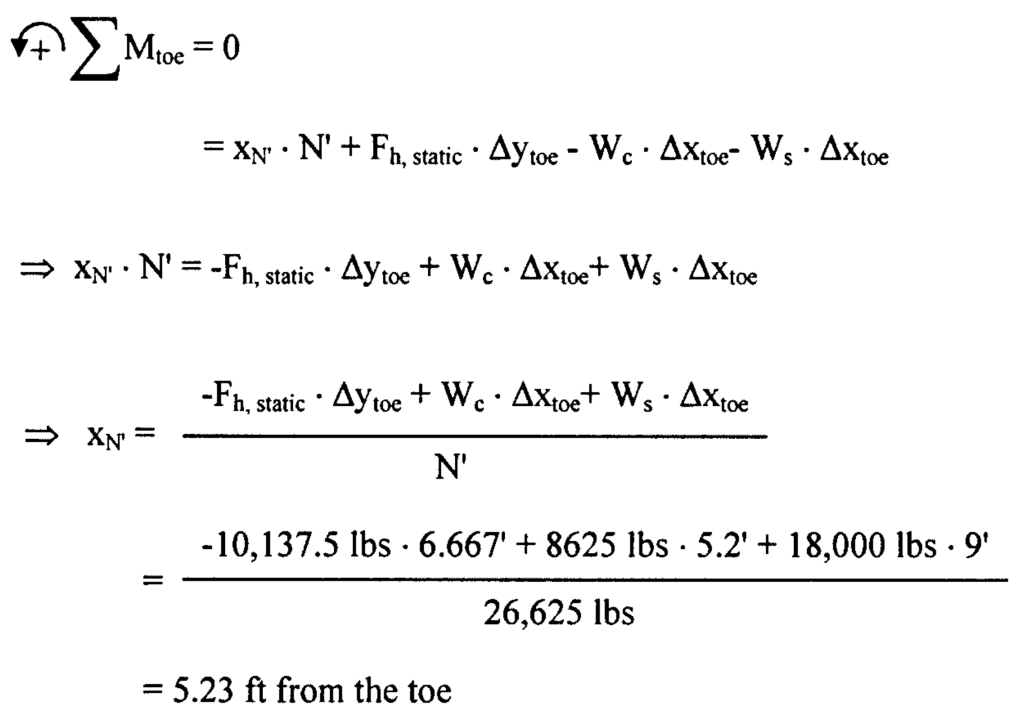

Turning to the sliding problem, the driving force is the earth pressure force and the resisting force is the maximum Coulomb friction of the base/soil interface. In this case the value of δ is equated to the unmodified value of φ’, although that isn’t always the case. (The basis for this is that there is a thin layer of backfill sand under the wall, under which is a different foundation soil.) We then apply Equation (1) and determine the factor of safety against sliding, which checks out against the Corps criteria.

Knowing the location and magnitude of the resultant, we compute the maximum and minimum pressures on the base. Since both pressures are compressive, the resultant is in the middle third, and thus we can proceed with the base design.

One thing that is missing from this analysis is a specific analysis for overturning. In this case we make a common assumption that, as long as the resultant force of the wall is within the kern and there are no negative pressures on the base, overturning will not be experienced. It is certainly possible to do an explicit overturning analysis to check this result.

Bearing Capacity Analysis

With the wall’s sliding and overturning established, we turn to the bearing capacity analysis of the base. The complete bearing capacity equation, from the Soils and Foundations Reference Manual (with modification,) is

(4)

where

- qult = ultimate unit upper bound bearing capacity

- sc, sγ and sq = shape correction factors. These are unity in this case since it is a continuous foundation (generally the case with retaining walls)

- bc , bγ and bq = base inclination correction factors (unity in this case since the foundation is level)

- Cwγ and Cwq are groundwater correction factors (unity in this case since groundwater isn’t an issue, a rare event with retaining and especially flood walls)

- Ic, Iγ and Iq = load inclination factors, discussed below

- Nc , Nq and Nγ are bearing capacity factors that are a function of the friction angle of the soil. Nc , Nq and Nγ are shown in the table below. These are handled differently when a slope is present. They are given in the Soils and Foundations Reference Manual. There is a general consensus for Nc and Nq but not Nγ. In this case we will use Vesić’s values for it, following AASHTO/FHWA practice. For this case the base soil φ’ = 40° we have Nc = 75.3, Nq = 64.2 and Nγ = 109.4

- Bf = Base width of the foundation. In this case, with an eccentrically loaded foundation, this must be reduced to the equivalent foundation width by the formula B’f = Bf – 2e = 13 – (2)(1.27) = 10.46’.

- q0 = overburden pressure on the base from the dredge (low) side of the wall. For walls such as this we neglect all effects of this, both any potential passive lateral pressure and overburden pressure.

- c = cohesion of the soil = 0

- Because of this and the previous point, we can neglect the first two terms of Equation (4) and only concern ourselves with the last one.

Load inclination is the result of two perpendicular loads acting on the base of the foundation. It is illustrated in the sketch at the left.

The load inclination factors are given as follows:

(5a)

(5b)

where the load inclination angle is given as follows

(6)

Substituting yields 𝞭’ = tan-1 (10,137.5 lbs/26,625 lbs) = 20.8°. The friction angle of the base soil proper is 𝟇 = 40°. Substituting into Equation (5b) yields l𝞬 = (1-20.8/40)2 = 0.23. We can neglect the factors for Equation (5a) as those terms do not apply to this situation, but for completeness lc = lq = (1-20.8/90)2 = 0.591.

Making all relevant substitutions:

- qult = (0.5)(1)(1)(0.23)(1)(10.46)(125)(109.4) = 16,450 psf

- Qult = qult Bf = (16,450)(10.46) = 172,067 lbs. = 172 kips

- N = 26,625 lbs

- FS = Qult/N = 172067/26625 = 6.46 (acceptable)

Settlement Analysis

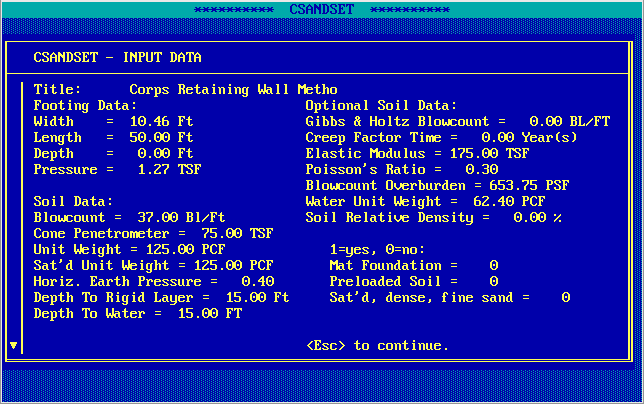

Settlement of retaining wall is an important topic, as settlement of walls and levees has led to overtopping (as we found out the hard way during Hurricane Katrina.) Instead of picking a method and doing it “by hand,” we will use the USACOE software package CSANDSET, developed by Virginia Knowles. To accomplish this we need to do the following:

- The foundation with we use is the reduced foundation width, or B’f = Bf – 2e = 13 – (2)(1.27) = 10.46’.

- The normal load is N = 26,625 lbs.

- The unit load on the foundation is thus 26625/(2000*10.46)=1.27 tsf (the units used by the program.)

- We assume a length of 50′; this puts the L/B > 10, which is an assumption for continuous foundations.

The input data is shown in the screenshot below.

The SPT and CPT are taken from “typical” values as they were not given in the problem statement. The option data is generated by the program. The horizontal (at-rest) earth pressure is Jaky’s Equation for normally consolidated soils.

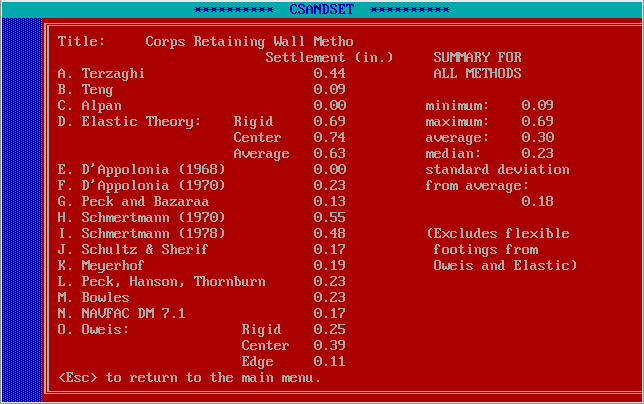

The solutions the program gives are as follows:

The various methods are described in the program documentation. Schmertmann’s Method is given a full description in Foundation Design and Analysis: Shallow Foundations, Settlement. Elastic methods are treated in Soil Mechanics: Elastic Solutions to Soil Deflections and Stresses and related posts. It is interesting to note the wide variance in results; this is typical of geotechnical methods in a state of flux, and can also be applied to bearing capacity of driven piles.

The supplemental data generated by the program is at the end of the post.

Dealing with Sloping Backfill

The example problem above has a level backfill. Sloping backfills–usually positive (up from the wall,) occasionally negative, are common with retaining walls. The problem of the sloping backfill is illustrated at the right.

Without going into the actual solution of the problem using a sloping backfill, the following changes must be made in order to accommodate the effects of this condition:

- The Rankine equation for sloping backfill needs to be applied. This can be found in the post Rankine and Coulomb Earth Pressure Coefficients. The coefficient computed is actually Coulomb theory applied without wall friction; the differences between this and “extended Rankine” theory for sloping backfill are discussed in the post on the coefficients.

- An additional region needs to be defined with the soil below the sloping backfill (assuming it’s positive) as shown in the diagram below.

- The length a of this region is already defined. The length b is given by the equation b = a tan (β). That length is important in a) computing the weight of the region and b) computing the additional length of the height the soil bears on the wall, or H + b.

- The backfill force must be separated into horizontal and vertical components, as shown in the diagram above. The vertical component actually increases both the weight on the foundation and the resisting moment of the weight.

Assuming a β = 10° and applying φ’mob = 25°, with the geometry shown we note the following:

- With the two angles shown, Ka = 0.462, which is higher than the level backfill value.

- The value of b = (8)(tan(10°))=1.41′. This means that the total height is 20 + 1.41 = 21.41′.

- The lateral pressure at the base is (0.462)(21.41)(125) = 1236.5 psf.

- The total lateral force on the wall Fh is (1236.4)(21.41)/2 = 13,236 lb/ft of wall. The resultant of that force is 21.41/3 = 7.14′ above the base of the foundation.

- That lateral force has a horizontal component of (13236)(cos((10°)) = 13,035 lb/ft and a vertical component of (13236)(sin(10°)) = 2298 lb/ft. The latter has a moment arm of 13′ from the toe.

- The area added by the sloping backfill has a weight Wba = (125)(8)(1.41)/2 = 705 lb/ft. Its centroid is located 5 + (2)(8)/3 = 10.3′ from the toe.

We will leave working out the effects of this backfill slope to the reader.

The Shear Mobilisation Factor (SMF) and Cohesive Soils

If we have soils with cohesion in the backfill, the cohesion should be modified in a similar way to the friction angle thus:

(7)

A more complete treatment of the SMF is given in Retaining and Flood Walls.

4 thoughts on “A Simplified Method to Design Cantilever Gravity Walls”